Philippe de Champaigne, Crucifixion, 17th century

The Crucifixion is a central image of the Christian religion; so central that we assume that it goes back to the beginnings, that it was always there. In fact, the Crucifixion as we've always known it -- as we see it in Phillipe de Champaigne's magnificent painting from the 17th century above -- appears surprisingly late in history, and almost not at all in early Christian art for many centuries.

The reason why the Crucifixion is so scarce in early Christian art is because it was shameful; a punishment meted out to common criminals, runaway slaves, and rebels. Roman citizens convicted of capital crimes were spared the agony and shame of crucifixion. They were beheaded, a comparatively merciful and dignified death. The crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth was a fairly routine execution by Roman standards, one more of many such executions throughout the empire every year. Crucifixion first appeared in ancient Persia and became a common form of execution in Rome. The condemned were nailed to a cross, or a post, or a tree, or sometimes to a wall, and left to die of shock and exposure; an ordeal that could last for days (thus Pontius Pilate's surprise to learn that Jesus was already dead before the day was through according to Mark's Gospel). Jesus was not the only famous person to die by crucifixion. It is possible that Spartacus, the leader of the great slave rebellion died by crucifixion. Crosses bearing condemned rebel slaves lined the Appian Way for many miles. Spartacus, unlike Jesus, was never betrayed and his body never identified. After the Jewish Rebellion of 70 CE, the hills around Jerusalem were forested with the crosses of executed rebels.

Crucifixion was a scandal.

The earliest surviving image of a crucifixion is not a work of art, but a work of vandalism; a crude school boy scrawl found on a piece of marble on the Palatine hill in Rome in 1857.

It came from the ruins of a boarding school for imperial pages founded by the Emperor Caligula. It could date anywhere from the first to third centuries. It says in crude misspelled Greek, "Alexamenos worships his god." It shows the unfortunate Alexamenos on the left before a crucified figure seen from the back with a donkey's head. It's certainly possible that Alexamenos was a Christian, but I wonder how likely that would have been in a very exclusive school for boys from very wealthy and noble Roman families within sight of the Imperial Palace. I think it just as likely that Alexamenos was the butt of cruel jokes that have always been part of boarding school life. This scrawl indicates something of the shame associated with crucifixion. Alexamenos prays to something so low a shameful as a crucified man with the head of a donkey.

The earliest surviving image of he Crucifixion of Christ dates from around 420 (a very late date, about 200 years after the first appearance of Christian art in the catacombs of Rome). It appears on a pair of wooden doors in the church of Santa Sabina in Rome, probably made on the orders of Pope Celestine I. Carved panels showing scenes from the Old and New Testaments decorate the doors. As is typical of early Western Christian art, the subject of these doors is Salvation History. The earliest surviving Crucifixion in art appears way up in the top left corner of the doors. The arrangement of the panels on the door has been altered many times, but it is unlikely that this small panel was ever very prominent.

And here is the very bowdlerized Crucifixion from the Santa Sabina doors. Early Christian art, even from the catacombs in the beginning, was very triumphalist. The earliest Christian art was about victory; of life over death, of good over evil, of Christ over the world. It was mostly about the Second Coming instead of the First Coming of Christ. Crucifixion and its shame and agony did not fit. Thus we see three men naked except for loincloths -- Christ between the thieves -- standing in front of a city wall instead of hanging from crosses.

Another very early surviving Crucifixion, almost contemporary with the Santa Sabina doors is this ivory plaque in the British Museum that once formed part of a small casket. It shows a very inexpressive Christ standing on a cross with we presume Mary and John, and someone on the right who appears to be mocking Him. The figure of hanged Judas on the left with his discarded moneybag appears much more dramatic. I wonder sometimes if the inexpressiveness of Christ here might be evidence of the lingering discomfort among a lot of ancients over the idea of a human God. Gods were not supposed to suffer or die.

An illustration from the Rabula Gospel book from about 586 shows the Crucifixion at the top and the events of Easter down below with the women at the empty tomb and the risen Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene. The Syrian artist who made this shows a much more violent Crucifixion than we've seen before with people appearing to attack a helpless Christ on the cross while soldiers sit on the ground and gamble for his clothes. Even so, His suffering is considered unseemly. A royal purple robe conceals His suffering body.

The crucifixion remained rare in early Christian art, but the Cross began to appear regularly and prominently after the 5th century. A cruel instrument of death originally made out of wooden poles or even just tree branches becomes a radiant celestial vision on the ceiling of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. This cross may only refer tangentially to the Crucifixion. What it really refers to may well be the Emperor Constantine's vision on the night before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge of a magnificent cross in the heavens with the words "By this sign you will conquer." The Cross becomes an emblem of victory and conquest written in the stars.

Among the most splendid of surviving celestial crosses appears in the apse of Sant' Apollinare in Classe just outside Ravenna. A jeweled golden cross appears in a blue nimbus full of stars.

This 8th century gilded bronze plaque, possibly from a Gospel book cover, came from near Athlone in Ireland. It's a Crucifixion that may be very loosely based on a panel painting brought from Rome. While possibly based on a Roman prototype, it is definitely an Irish interpretation of a Christian subject. Christ appears as a huge impassive figure on the Cross magnificently arrayed in spiral and interlace patterned robes like an ancient Irish chieftain. Two figures below appear to torment him while winged figures we assume to be angels fly above. The ancient Irish like many northern European peoples may have conceived of Christ as a great warrior chief, an epic hero, leading his loyal soldiers to battle with Satan and his legions. The Crucifixion for them may have been a kind of heroic battlefield self-sacrifice, or a feint to lure the devil into a trap.

The magnificent Muiredach High Cross from the 9th century stands in the remains of the Monasterboice monastery in County Louth, Ireland.

It shows on one side a larger and more splendid version of the Athlone Crucifixion surrounded by pre-Christian spirals and interlaces that were believed to have magical powers. The Christian cross itself stands surrounded by a pre-Christian Irish sun circle. The pain and torment of the Crucifixion becomes subsumed in an even more ancient power and glory with magical powers.

On the other side of Muiredach Cross appears the Last Judgement; among the earliest pairings of the Crucifixion with the Final Reckoning, but certainly not the last.

By the 10th century, Christianity starts to appear in fits and starts in the Viking lands. The Jelling Rune Stone was put up by King Harald Bluetooth of Denmark as a memorial to his parents and to his conversion to Christianity. The Crucified Christ appears embedded in a seething mass of serpentine interlace pattern.

Also in the 10th century, before King Harald Bluetooth erected the Jelling Rune Stone, the first Crucifixions in the form that we would recognize are made in Germany. The familiar image of the Crucifixion -- a cross with a suffering figure of a dying Christ hanging from it -- appears suddenly and fully formed in the German Rhineland in the 10th century. The earliest surviving example predates the Jelling Rune Stone and was commissioned by Archbishop Gero of Cologne. It still stands in the cathedral.

Only the corpus of the Gero Cross survives. The present cross and setting are all recent. It is a startling apparition in the wake of all the celestial crosses, bowdlerized Crucifixions, and warrior chieftains of earlier versions. Christ visibly and unmistakably suffers. The body hangs and sags. The head bows under the weight of pain and suffering. All the earlier cautions and scandal that originally surrounded this central event of the Christian legend suddenly and inexplicably (to me anyway) vanish.

This new suffering crucifix spreads rapidly across northern Europe. Here is a splendid page from the 10th century Ramsey Psalter from early medieval Britain.

This new emotional appeal of shared suffering quickly supplants or merges with the older celestial cross of Constantine's vision.

Cross of Lothair, front

This cross was possibly made for the Emperor Otto III around the year 1000, and was a processional cross used in the coronation ceremonies of Holy Roman emperors. The jeweled front of the cross with an ancient cameo of the Roman Emperor Augustus in the center faced the emperor during the ceremony. It is the jeweled cross that appears in so much early Christian and Byzantine art, the glorified celestial cross of Constantine's vision.

Cross of Lothar, reverse

The back of of the Lothair Cross is a flat piece of gold that faced the bishops during the coronation ceremony. Engraved on the back is a very beautiful and moving variation on the suffering Christ on the Cross first seen in the Gero Crucifix a century earlier. For the first time, the whole Trinity appears in a Crucifixion. The hand of God the Father reaches down with a wreath of victory. Inside the wreath is the dove of the Holy Spirit. Coiled around the base of the cross is the serpent of Satan, the tempter of Adam and Eve in the story of the Fall in Genesis.

From the Daphni monastery, 12th century

Mosaic from Hosios Loukas monastery, 12th century

The Crucifixion rarely plays a central role in Byzantine art that it does for Western Christian art. Byzantine art with its very specific formulas and gold backgrounds is always about an eternal present tense. These are not scenes from a historical past, but always from a spiritual present viewed through the window of an icon or a mosaic. The powers of Heaven show these for the instruction and salvation of mortals. The Crucifixion plays only one part in the vast eternal Divine Liturgy in the realms of Heaven. The center of that eternal Liturgy is always Christ Pantocrator, Christ the ruler of All Things reigning from His celestial throne.

Icon from Novgorod, Russia, ca. 1360

San Damiano Cross, 12th century

The Tuscan painted cross is Byzantine form adapted to the needs of Western Latin Christianity with its emphasis on Salvation History. We think of these as Byzantine, but they are not. They are very specifically Western. Painted crosses hung over altars or stood on rood screens to explain the Mass to congregants in the church. Their image is narrative as much as it is liturgical. There is not that same theology of icons as glimpses into the realm of Heaven behind Byzantine imagery. The painted cross preaches and teaches in the tradition of Western narrative religious imagery.

Above is the famous Cross of San Damiano that supposedly spoke to Saint Francis of Assisi commanding him to restore the ruined church in which it originally hung.

Circle of Giotto, The Cross of San Damiano Speaks to Saint Francis, fresco in the Upper Church of San Francesco, Assisi, 14th century.

Italo-Byzantine painted cross from Pisa, 12th century

Both of these painted crosses from Pisa above and below show the Christus Triumphans and the Christus Patiens surrounded with narrative imagery of the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ.

Italo Byzantine painted cross from Pisa, 13th century

Painted cross attributed to Cimabue, 13th century, Arezzo

Time has not been kind to the works of Cenni di Pepi, better known by his unflattering nickname Cimabue which means "Ox Head." The textbooks on Italian Renaissance art, taking their cue from Vasari and his Lives of the Artists, begin with Cimabue. In fact, Cimabue's art is not a beginning, but an end, a splendid sunset of the long Italo-Byzantine tradition just before its end. Cimabue was among the great conservatives of art, breathing a whole new life into traditional formats.

Cimabue, painted cross from Santa Croce, Florence, 13th century; former state before 1966

Perhaps the greatest of all the painted crosses of Tuscany is Cimabue's now ruined cross that once stood on the rood screen of the great Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence. Cimabue reduces the painted cross down to its most basic parts; the body of Christ hanging on the Cross between his Mother and the Beloved Disciple. Against the hard geometry of the Cross, Christ's body sags in a magnificent S curve from the head to the feet. It is a moving image of spiritualized suffering. The abstracted forms in no way detract from our emotional participation in this image. At the same time, the formalization universalizes this one moment of intense pain, raising it up out of the particular to make it stand for all suffering.

Cimbue, painted cross in Santa Croce in its current state.

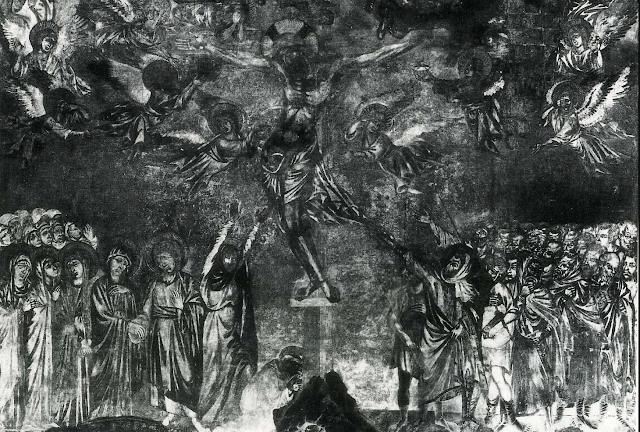

Cimabue, fresco in the Upper Church, San Francesco, Assisi, 13th century

This is the ruin of a once famous and influential fresco painting by Cimabue in the Upper Church of San Francesco in Assisi. The artist painted this fresco using what were originally very bright colors that proved to be chemically volatile over time. The once brilliant whites of the highlights all blackened while the once deep shadows faded into a pale ocher creating an effect like a photo negative.

Photo negative of Cimabue's fresco in Assisi

Indeed to get some dim sense of what this painting might have looked like, some books publish it in photo negative. This is the sad ruin of a once magnificent painting. A giant figure of Christ dies majestically on the Cross in contrast with the crowd of small figures of those who mourn and those who mock His dying. That enormous figure of the dying God fills the top half of the picture surrounded by grieving angels. Cimabue turns a routine execution in ancient Rome into a cosmic tragedy.

This painting was once very famous and influential. We can see its echoes throughout Italian art for generations.

We can see the influence of Cimabue's great painting on the Crucifixion on the back of Duccio's great Maesta altarpiece for the Cathedral of Siena. The composition is very similar, but Duccio's emphasis is less on cosmic tragedy and more on human suffering; by the dying Christ along with the two thieves, and the grieving mourners on the left.

Giotto, painted cross in Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Giotto, painted cross from Santa Maria Novella, Florence, 14th century

Instead of a magnificent hieroglyph of divine suffering, Giotto returns to the spirit of the Gero Cross in Cologne from 4 centuries earlier. Giotto's painted cross pays homage to Cimabue's great cross while departing from the Italo-Byzantine tradition that shaped it. The body sags with almost palpable weight from the hard geometry of the Cross. Suffering writes itself on this body with prominent ribs and abdomen protruding with collapsed organs. Giotto seeks to move us emotionally by appealing to our experience of the world.

Giotto, painted cross from the Tempio Malatesta in Rimini, 14th century

Pietro Lorenzetti, fresco in the Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi

Altichiero, fresco in the Santo, Padua

Donatello

This wooden Crucifixion by Donatello has jointed shoulders so the figure can be taken down from the Cross and symbolically laid to rest during Good Friday liturgy.

Donatello

A late work by Donatello that personalizes the sense of cosmic tragedy pioneered by Cimabue.

Antonello da Messina

The Limbourg Brothers

Jan Van Eyck and assistants

A detail from the Crucifixion panel in Jan Van Eyck's diptych showing both a strikingly suffering Christ on the Cross against a superb landscape background that shows a river valley, a distant range of snow-capped mountains, all kinds of clouds, and a daytime moon.

The mourning women from the Crucifixion wing of Jan Van Eyck's diptych.

Details from the Last Judgment wing of Jan Van Eyck's Diptych.

Rogier Vand Der Weyden

The rigidly fixed body of Christ nailed upon the cross in Rogier Van Der Weyden's work contrasts with the windblown loin cloth. Those waving bits of cloth only emphasize the rigid torment and pain of Christ nailed onto the Cross. That's certainly true in the Viennese triptych above, and even more so in the striking and austere large diptych in Philadelphia below.

Rogier Van Der Weyden

Veit Stoss

Rogier Van Der Weyden would influence artists all over Europe, even in Italy. His conception of the Crucifixion as the body of Christ rigid in torment with that rigor heightened by a windblown loincloth had a big influence on sculptors in northern Europe. Among the best variations on Rogier's idea is in the church of Sankt Sebaldus in Nuremberg by Veit Stoss.

Pestkreuz in Cologne, 14th century

"... they pierce my hands and feet; I can count all my bones"

The Pestkreuz was an extreme emotional manifestation of suffering and torment.

Mathias Grünewald, Isenheim Altar

The Pestkreuz inspired probably the most violent and lurid depiction of the Crucifixion ever by the great and mysterious painter Mathias Grünewald. He painted it not for a church, but for the altar of a hospital ward that treated plague victims and those suffering from ergotism, now a rare disease, but once common in a region of Europe where rye bread was a staple, and bread made with rye contaminated with a toxic fungus made ergotism widespread.

I wrote a whole post on the Isenheim Altarpiece that you can read here.

Albrecht Dürer, woodcut from The Small Passion

Albrecht Dürer, from the Engraved Passion

Michelangelo

Michelangelo

Titian

Tintoretto

El Greco

Adam Elsheimer

Peter Paul Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens

Velazquez

Rembrandt

Rembrandt

Rembrandt

Santo from New Mexico, 18th century

Retablo in the Chimayo Sanctuary, New Mexico

Molleno, Christ of Esquipulas in the Chimayo Sanctuary, New Mexico, before 1855

Pierre Paul Prud'hon

Eugene Delacroix

William Blake, 'Albion Adoring Christ', end piece to Jerusalem

Caspar David Friedrich

Carl Bloch

Leon Bonnat

Henry Ossawa Tanner

James Tissot

Thomas Eakins

Chinese Christian painting, 20th century

Lovis Corinth

Emil Nolde

Henri Matisse, Stations of the Cross from the Chapel of the Holy Rosary, Vence, France

Marc Chagall

Michael Rothenstein

Stanley Spencer

Francis Bacon

Barnett Newman, Stations of the Cross in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Barnett Newman, Third Station of the Cross, 1960

The Rothko Chapel with paintings by Mark Rothko that were originally intended to be a series of Stations of the Cross for a Catholic chapel.

An African Crucifixion from the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Nativity,

Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

Murals in the Episcopal Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Port Au Prince, Haiti

Edwina Sandys, Christa in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York.

Erik Ravelo, The Untouchables

No comments:

Post a Comment