"Hier ist's richtig!"

(Here, it's alright!)

--slogan on the Eldorado Bar

The Brandenburg Gate lit up for Gay Pride in 2010

The same view in 1928

Berlin had the biggest, liveliest, most varied, and most politically active gay subculture in the world from roughly 1880 to 1933. It was in Berlin that the cause of gay political and social emancipation was born. Never did that subculture sparkle more brilliantly than in the last decade before its sudden death in 1933.

Berlin in 1928

Potsdammer Platz at night, 1931

Men dancing at a club in Berlin sometime in the 1920s

Who loves a sailor?

Women dancing at the Eldorado Bar in Berlin

The Eldorado Bar, Berlin

Miss Eldorado

Die Freundin, a newspaper for lesbians. There were a number of gay publications in Berlin. Die Freundschaft and Insel were for gay males. There were numerous guidebooks to Berlin's gay nightlife; bars, bath houses, cabarets, cruising grounds, and even prostitutes.

EXTRA:

It turns out that there were as many as 33 different weeklies and dailies for gays and lesbians published in Weimar era Berlin, still a very impressive number. It's all the more impressive since Paris had only one gay publication, and in the entire English speaking world there was only Henry Gerber's short lived Friendship and Freedom published in Chicago.

A portrait by Christian Schad from 1927 of a minor aristocrat Count St. Genois d'Anneaucourt with a woman and a transvestite. This portrait shows another venue of Berlin nightlife, especially its gay nightlife, rooftop parties.

One of the most popular and famous Berlin dance bands was Marek Weber and His Orchestra. They were an international group of musicians. Weber was Czech and many of his musicians (especially his lead singers) were Jewish. They played at the swankier nightspots of Berlin including the larger and swankier gay nightclubs.

EXTRA:

Another major feature of gay Berlin was sexual tourism after World War I.

Among the most famous such tourists were the three pictured above, WH Auden, Stephen Spender, and Christopher Isherwood who were all fondly remembered by the legions of male prostitutes in Berlin for their generosity (Auden and Isherwood even helped boys evade capture by the police and helped out one escapee from jail).

Police mugshot of a boy prostitute from 1931

Prostitution was a huge industry in post World War I Berlin, especially with the economic collapse that followed the War that wiped out the savings and livelihoods of the German middle class. While Paris was famous for its women for sale, Berlin was particularly famous for the availability of its boys. Beachy cautions that all sexual contact between men in Berlin was officially illegal and unofficially illicit, so that finding any clear line between sex and sex for sale is very difficult. Almost all sexual contacts involved some kind of quid pro quo, and the motivations of both rent boys and their customers could be varied and complicated. Beachy and others from the time estimate that about a third of Berlin's rent boys were straight; that they were forced into the trade by economic necessity, or hustled to supplement meager wages. Some of the gay rent boys were in it only for the money, but others hoped to find love or at least a caring sugar daddy. Remarkably, blackmail which was so common a part of the hustler's trade before the War largely disappeared from Berlin after the War. Extortion became bad for business, especially with the tourist trade. Most customers wanted casual sex, but others (such as Auden and Isherwood) formed friendships and even had love affairs with their trade.

A scourge of the gay demimonde then as now was drug abuse. The drug of choice in Weimar era Berlin was cocaine, also a Berlin invention.

That all this flourished in Berlin is miraculous. Throughout its whole history, the Berlin gay subculture labored under a series of heavy prohibitive laws forbidding just about everything it did. The most notorious of all was Paragraph 175 of the German penal code, passed by the Reichstag in 1871 that criminalized all sexual contact between men. Paragraph 175 was the harsh Prussian anti-sodomy law writ large for the newly forged German Empire. There were no laws prohibiting sex between women only because most European states agreed with Queen Victoria who believed that such a thing was not possible. There were strict prohibitions on public cross-dressing in Berlin as in most cities. On top of all that was the 19th century bourgeois proscription of sex from all aspects of life except for the most intimate. Adultery by women (but not by men) and sex between men were considered the worst and most unspeakable crimes against decency. The only respectable thing to do when caught in flagrante delecto was to commit suicide.

So why Berlin of all places? Early nineteenth century Berlin was a military garrison town and a university town with a lot of young men. It was an open secret that soldiers would frequently supplement their meager military pay with prostitution. There was a lively male sex scene in Berlin at least since the early 19th century and probably going back to the 18th century. The German Romantic cult of friendship fed into this sexuality as well. When Berlin became the capital of the new German Empire, and the Reichstag passed Paragraph 175, the local police department decided that the new law was simply unenforcible. A succession of police chiefs decided that the evidence requirements of a criminal trial made such a law almost impossible to prosecute. And so, the Berlin police made a very permissive and even indulgent policy towards Berlin's gay community. Blackmail was always a constant threat to gay men, especially with the looming threat of Paragraph 175. The Berlin police would sometimes arrest the blackmailed on sodomy charges, but they would more frequently arrest the blackmailer and prosecute him for extortion. The extortion charge was usually the easier to prosecute successfully than the sodomy charge. The Berlin police department's attitude toward Berlin's gay community was so permissive that they even gave VIPs tours of the city's gay nightlife.

***

I am currently reading Robert Beachy's fascinating new book Gay Berlin; Birthplace of a Modern Identity. That Germany in general and Berlin in particular are the birthplace of Gay as an identity and as a social and political movement is widely known; but until now, that specific history as well as the questions of why and how were left mostly to what Joe Jervis of JoeMyGod calls (sometimes derisively) The Gay Studies Department. Those origins go back much further than the Weimar Republic and 1920s Berlin, even back to before 1870 and the formation of the German Empire under Prussian domination; certainly before Paragraph 175. The emergence of a modern gay identity was closely bound up with the emergence of a German national identity and the politics of unification in the 19th century. Before 1933, and even before the First World War, Berlin was in the vanguard of the emancipation of sexual minorities and of sexuality in general. The impact of Berlin on the formation of a Gay identity, gay subcultures, gay political movements, and on the very idea of gay emancipation would eventually become global.

The Munich Odeon as rebuilt after World War II

On August 29, 1867 a young lawyer by the name of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs took to the stage of the Munich Odeon to address a convention of jurists. He called for the repeal of anti-sodomy laws throughout Germany arguing that same-sexual activity was the manifestation of an orientation, a natural variation, and not actions born of moral lassitude. He was booed and heckled off the stage. Even though Ulrichs could not finish his speech, his was the first public argument in history for the reform of laws based on the idea of a homosexual identity.

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

Ulrichs' attempted speech brought into the open a painful personal struggle that began a public political transformation. Five years before his speech in Munich, Ulrichs told his family about himself and his desires, the first man to "come out" privately and later publicly. He already had his first homosexual experience at age 14. He noted the wide gulf between his own experiences and the conventional and traditional descriptions of same sex activity. He began writing and publishing about that chasm arguing that a sexual preference for one's own gender is innate and not some willful choice. Further, he argued that not only is it innate, but that it is natural and harmless, and as authentic in its love as conventional male-female attraction.

His publications began to attract correspondence from many young men writing anonymously or under pseudonyms from around the German speaking world who had similar experiences and struggles, many with thoughts of suicide. The high suicide rate among such men goaded Ulrichs to publish and eventually to speak out publicly.

Ulrichs as a jurist was deeply involved in the politics of German unification. The brutal suppression of the 1848 Revolution and the abject failure of the Frankfurt Parliament ended hopes for Germany united as a liberal republic. German unification was considered inevitable; however, the question remained as to whether a united Germany would be a few states under the domination of Prussia (The Kleindeutsch party), or whether Austria together with many other states would be included to counter Prussian ambitions (The Grossdeutsch party). Ulrichs, along with most other German liberals, favored the Grossdeutsch party. In addition, Ulrichs and other gay men feared the severe Prussian criminal code that penalized all sexual activity between men. The German states were a patchwork of laws regulating sexual relations. Many (such as Ulrichs' native Hannover) had no laws on the books to penalize sodomy or other same sex activity, and yet the social and economic consequences for such activity could be severe. Ulrichs lost a prominent position as a jurist in the employ of the Prince Elector of Hannover when he identified publicly as gay. The cause for gay emancipation became closely bound up with German liberalism and with more liberal and democratic left-wing political parties, especially with the Social Democrats.

Ulrichs was the first coin a name for this new identity based on sexual orientation. He called men attracted to other men "Urnings" after the god Uranus. He got the idea from Plato's Symposium where there is an argument over the parentage of the goddess Aphrodite, whether the male Uranus or the female Dione is her true parent. Ulrichs referred to heterosexuals as "Dionings."

In 1869, the author and human rights activist Karl Maria Kertbeny, a correspondent with Ulrichs, first coined the terms "homosexual" and "heterosexual." As Beachy argues in his book, the term "homosexual" along with the identity it described was created not by government psychologists eager to classify a pathological class, but by reformers and gay men themselves. And even those psychologists who did describe homosexuality as pathological such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Sigmund Freud urged decriminalization and legal reform.

Beachy takes no position (so far as I've read in his book) in the academic war between those partisans of Michel Foucault who believe that homosexual orientation was a "creation" of 19th century psychologists and reformers, and the followers of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld who claim that theirs was a "discovery" of something that was always there.

Since I lived most of my gay life outside the academy, I agree with the Hirschfeld party. What Ulrichs first described, Kertbeny named, and Hirschfeld argued is natural describes my own experiences better than Foucault's positive embrace and inversion of more traditional descriptions of homosexuality.

Magnus Hirschfeld

The late 19th century saw the birth of sexology with such prominent names like Krafft-Ebing, Havelock Ellis, and Auguste Forel taking on the question of homosexuality, its nature and origins. Most concluded that homosexuality is indeed innate and somehow biologically determined. Many like Freud and Krafft-Ebing continued to describe it as pathological, if not exactly criminal.

The pioneering sexologist who broke with this consensus was Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld.

Hirschfeld not only believed that homosexuality was biologically determined, but that there was nothing wrong with it. Homosexuality was not a pathology, but a natural variation, he claimed, and so he told his many patients. He counseled patients who came to him with concerns over their sexuality to accept it and to make the best of it. Hirschfeld believed that homosexuality was a kind of "third sex" or intermediate sex, that the gender binary between male and female is not nearly as clear and hard as conventional wisdom assumes. He soon discovered that there was a whole range of "intermediate sexes" beyond homosexuality that included cross-dressing and what we would call transgender (a modern anachronism). The most original and radical part of all of his work was his declaration that there was nothing wrong with any of it, that none of this variation was in any way pathological. The problems his patients suffered, he argued, were not from the sexual variation, but from legal and social oppression. He urged his patients to find others of their own kind, to organize, and to fight for political emancipation.

Hirschfeld was a true-believing liberal who embraced the whole cause of sexual emancipation from women's suffrage to the repeal of Paragraph 157 to social and legal acceptance of transgendered people. He urged lesbians to organize, and he even successfully negotiated some relief for the plight of cross-dressers and transgendered people who were penalized by Berlin's ban on public cross-dressing and police harassment. He persuaded the police to issue permits for cross-dressing in public.

Adolf Brand

A 1920 edition of Adolf Brand's Der Eigene

Adolf Brand represented a very different and in some ways more radical and separatist version of gay emancipation from Magnus Hirschfeld.

Brand broke with Hirschfeld's very liberal and inclusive vision of gay liberation to argue that male on male attraction is not just normal or natural, but is a positive good, even to be preferred over heterosexual attraction. Brand believed that gay male life found its fullest expression not in some same sex replica of conventional marriage and family life, but in what he called the Männerbund, the society and culture of men, in male fraternities such as the military, youth organizations, in male friendship carried fully into male on male eroticism.

Brand's vision was very anti-liberal. The Männerbund vision of gay male life was openly misogynistic, antisemitic, and tied to some of the more extreme and tribal forms of German nationalism. Brand modeled his very male supremacist version of gay life on ancient Greece (or on 19th century reconstructions of it). As in ancient Greece, bonds between men were supposed to be deep, intense, and ultimately transitory, and did not rule out conventional heterosexual marriage in order to produce more male offspring. Brand himself was married to a woman, and remarkably, the marriage lasted.

Brand published a paper which he called Der Eigene, a title that is hard to translate into English. It basically means something like The Singular, but with a more personal connotation like "One's Own." It featured photo spreads of beautiful young men in various stages of undress along with essays and articles by Brand and other sympathizers. Brand was not the least bit shy about the erotic part of homoeroticism.

Brand had ties to the German youth movement founded in 1896 called Wandervogel. Wandervogel or "Wandering Bird" began as an informal and apolitical youth group devoted to hiking, camping, and outdoor sports. One of the members of the very first Wandervogel group came out as homosexual and fully embraced Brand's Männerbund ideas and expanded upon them.

Hans Blüher in 1906

Hans Blüher later in life wrote a three volume history of the Wandervogel movement. The first two volumes were highly praised. The third discussed homosexuality in the movement and was roundly attacked from across the political spectrum. Radical right wing German nationalists attacked Blüher's and Brand's ideas of Männerbund as every bit as degenerate as Hirschfeld's advocacy of homosexuality. Liberals attacked Blüher's writings for their misogyny and antisemitism. Women formed their own Wandervogel groups in reaction to Blüher's assertion that women had no place in the movement. More liberal Wandervogel groups began admitting women.

A Wandervogel troop

Wandervogel boys working out au naturel

Wandervogel was one of many self-actualization movements in late 19th century and early 20th century Germany that might appear familiar to us. There were nudist movements, vegetarian movements, all kinds of health movements, and spiritual improvement movements. New Age was a reality in Germany long before the term was coined in the English speaking world. All of these movements frequently blurred into each other, and homosexual emancipation was part of this. But then, so was German nationalism. Spiritualist movements sometimes became mystical "blood and soil" nativist groups with attempts to revive pre-Christian German religions; something that Nazi ideologues such as Alfred Rosenberg would exploit. Wandervogel troops would sometimes evolve into more liberal international Scouting organizations, but just as frequently they laid the groundwork for the Hitlerjugend.

Hirschfeld rejected the whole Männerbund movement as much as it rejected him. Hirschfeld was Jewish and he welcomed women as patients and as colleagues.

Helene Stöcker

Hirschfeld enjoyed a lot of enthusiastic heterosexual support (which Brand did not). Among his most important allies was the pioneering feminist Helene Stöcker. Though Stöcker was heterosexual, she supported fully homosexual emancipation and joined forces with Hirschfeld to successfully defeat a bill pending in the Reichstag to criminalize lesbian sexuality in 1909.

In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee for the purpose of repealing Paragraph 175 from the German penal code. He submitted the first petition to the Reichstag in 1898 and again every year until 1933. Among the signatories to the petitions were a number of prominent people such as Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, Martin Buber, Käthe Kollwitz, Rainer Maria Rilke, Stefan Zweig, and Richard Krafft-Ebing. Hirschfeld won a growing number of allies from the Social Democrats, though the party as a whole did not endorse the petition.

The villa north of Tiergarten Park near the Reichstag in Berlin that housed the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (The Institute for Sexual Science).

In 1919, Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin, a pioneering center for research and for political and social advocacy. The institute included research facilities, a library, a museum, a social center, treatment facilities, and a surgery. The first gender reassignment surgeries were performed at the Institute. The first gender reassignment operation was performed on a decorated German officer who remains anonymous in the surviving records. The Institute kept a locked box outside its gate for people to submit their questions about sex in secret. The vast majority of those questions came from heterosexual couples asking about birth control or abortion services. The Institute included family planning for heterosexual couples.

The Institute produced films to educate the broader public about sexuality in general and about homosexuality in particular. The most famous of them starred another heterosexual friend of the Institute, the actor Conrad Veidt, a very generous man who made a career playing movie villains from Cesare the murderous sleep walker in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari from 1919 to Nazi Major Strasser in Casablanca in 1942. Veidt played a famous concert violinist who has an affair with a student in the film Anders als die Andern (Different from Others), 1919, the first film to portray a gay relationship sympathetically. Hirschfeld himself appears in the film.

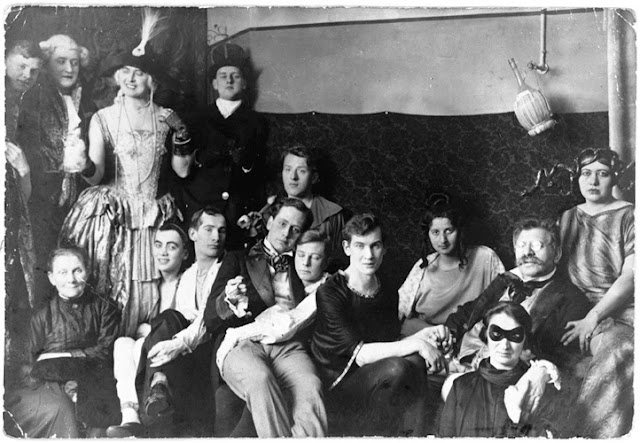

A costume party at the Institute with Hirschfeld seated on the right; one of my favorite photographs from the period.

The motto of the Institute was Per Scientiam ad Justitiam (Through Science to Justice). Hirschfeld believed that it was his life's work to combat ignorance and superstition surrounding sex, to change conventional wisdom and the laws based upon it, and to undo the harm that such bigotries caused. He had a very liberal faith in the ultimate reasonability of people. Do the research, present the evidence, and reasonable minds must change or at least reconsider. Of course, not all minds are reasonable, and eventually much darker and stronger passions of fear, vengeance, and tribe took over. Hirschfeld found himself to be the constant target of threats. He was attacked, beaten, and badly injured on a street in Munich.

In 1933, the lights went out.

Shortly after the Nazi takeover, the Institute was closed, looted, and its library and archives publicly burned. Most of those photos and film clips of Nazi book burnings show the destruction of the Institute's library.

Magnus Hirschfeld fled Germany and lived in Nice in southern France where he died of a heart attack in 1935.

Adolf Brand and his wife were killed in an Allied air raid in February 1945.

Hans Blüher died in obscurity in 1955.

Unknown thousands upon thousands of lesbians, gay men, transgender, and bisexual people died at the hands of the Nazi regime, at the hands of their neighbors and fellow soldiers, and in the course of the war from 1939 to 1945.

A surviving pink triangle from a prison uniform

***

The legacy of Gay Berlin is still with us and still informs a lot of the arguments over gay identity today.

Magnus Hirschfeld remains the father of mainstream of gay civil rights and gay liberation in the Western world and beyond. His broadly liberal outlook envisioned an ever expanding coalition seeking recognition and acceptance by legitimate society of sexual minorities. So much of his work is now dated. Many liberal gays and lesbians together with more radical gays and lesbians question the very idea of a "cause" for homosexuality. Biology has largely discarded the determinism that dominated the scientific thinking of his day. But, Hirschfeld's courage, advocacy, and generosity of spirit continue to inspire activists from San Francisco to London to Moscow to Kampala.

Adolf Brand has his legacy too. Certainly he continues to speak to that affluent minority of gay men and lesbians who crave admission into the dominant classes. But, his Männerbund also speaks to gay radicals and separatists despite his misogyny and supremacism. Like radical gay men and lesbians of today, Brand emphasized what was truly distinct about homosexual relations and culture, that it was something wholly other from conventional heterosexual dominated culture. Like gay radicals today, Brand too believed that homosexuals should create their own models for living together instead of mimicking or adapting heterosexual marriage and family life.

5 comments:

Thank you for this fascinating history!

The video links for Weber are from my YouTube account. My channel centres on Gay and Jewish performers from this time. jonjamg

If you're interested in the music of gay and Jewish performers from 1920s and 1930s try my YouTube channel - jonjamg. The Weber songs here are from it.

A bit late, I guess, but Conrad Veidt wasn't heterosexual--he was as bisexual as can be :) Just chipping in here as a fan and it's mentioned in various sources that he loved both women and men. And apparently walked the streets himself in drag a few times, somewhere around 1919. Just additional trivia there for you--great article and fascinating pictures!

Thank you for the interest post ("Berlin; Where Gay Began"). I'm about to have a book on gay life in Chicago published and would like to use the photo of Hirschfeld at the costume party that you include. Do you know where it came from? (My publisher is requiring that I try to find the copyright holders of all the illustrations I'm using in the book. I would like to use it.) Any help will be much appreciated.

Jim Elledge--jim.elledge@gmail.com

Post a Comment