Tuesday, March 21, 2017

Lenten Thought

If you need the fires of hell to terrify you into being a good person, then you probably aren't and never were.

Saturday, March 18, 2017

Artists' Berlin 3

In 1913, a book and magazine illustrator named Ludwig Meidner made a remarkable series of paintings one right after the other in a kind of fever pitch. He never made anything like these again. He went back to illustrating, eventually dying in obscurity in London shortly after the Second World War. They are all scenes of violent apocalyptic destruction where the sky and the ground are rent by unknown forces. These paintings all look remarkably like the air raids that would begin in the First World War and become a hallmark of the Second World War. The ground shakes and buildings explode. Great glowing things fly through the sky and seem to drop explosives everywhere. But, there are no planes or any weapons of any kind visible.

In 1913 - 1914, many people obsessed over some kind of coming apocalypse from mystics like Helena Blavatsky's Theosophical followers to ardent materialists like Filippo Marinetti to Theodore Roosevelt. All three of those very different people welcomed the anticipated End of the World as a necessary purgation, as a kind of redemption and reinvigoration through violence. Peace and prosperity they all agreed bred corruption and dissipation. "War, the world's true hygiene" said Marinetti. Once the First World War started, Theodore Roosevelt clamored to get the USA actively involved in it. Roosevelt's youngest son Quentin died in combat in 1918. Roosevelt was inconsolable and died a year later. Marinetti lost many of his friends and colleagues in the War, and afterward eagerly embraced the emerging Fascist movement and became a speech writer for Mussolini.

In August 1914 to November 1918, the world did indeed end, though not as people anticipated.

Ludwig Meidner, Apocalyptic Landscape, 1913

I've seen two of Meidner's remarkable apocalyptic paintings. I saw the very striking one above in the Landesmuseum in Münster which turns out to have a very fine collection of German early 20th century art.

I saw the one below many times in the Saint Louis Art Museum, another museum that has a very fine collection of German 20th century art.

Ludwig Meidner, Burning City, 1913

German artillery on parade through the Brandenburg Gate in August, 1914

Severely wounded German war veterans march in protest on the War Ministry in November 1918.

In Germany a generation was decimated and the world turned upside down. The German war effort ended in economic collapse brought on by sanctions and the expense of the war; and, in mutinies and uprisings by soldiers and workers bearing the brunt of the suffering. The Kaiser abdicated, and General Ludendorff who effectively ruled Germany from the front lines, ordered the long marginalized left wing Social Democrats to form a republic, perhaps in hope of getting better terms from the allies during armistice negotiations. In the end, there were no negotiations. Germany was presented with an ultimatum to surrender unconditionally. The new republican government was too weak to refuse the demands. And so, Germany was declared the official loser of the War.

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

The mass industrialized death created by new mechanized warfare, the pointlessness of the War, and the lies created to justify its waste infuriated young men in all the countries touched by the calamity, especially its veterans.

Few artists came out of the War more angry than Otto Dix.

Dix was one of the few modern artists who did not come from a bourgeois background. His father was an ironworker and his mother was a seamstress. In 1914, he eagerly signed up for military service when the War broke out, as did so many young men in Europe. He served all through the War to 1918. He participated in some of the fiercest fighting in the Somme, on the Eastern Front, and in the Spring Offensive of 1918. He was badly wounded in the neck at one point, and was awarded the Iron Cross for his service.

These details say nothing about the effect that the War had on Dix. After he left military service, he complained about sleepless nights, terrible nightmares, and flashbacks; things all very familiar to us that we would describe as post traumatic stress syndrome, but back then were known as shell-shock.

He spent many years after the War externalizing the shock and horror of the War in his art. He made a powerful series of 50 etchings called The War, perhaps inspired by Goya's Disasters of War. He recorded things he saw and experienced in these etchings.

Otto Dix, "Advancing Under Gas" from The War, etching, 1924

Otto Dix, 'Corpse in Barbed Wire,' from The War, 1924

Otto Dix, "Dead Men Before the Position near Tahure", etching from The War, 1924

Otto Dix's war recollections culminated in a large triptych also called The War painted in 1924. Like Käthe Kollwitz, Dix resorted to Christian imagery to try to articulate a profound experience and the rage and sorrow it caused him. Here Dix uses not so much a particular Christian subject (such as Kollwitz's re-imagining of the Pieta), but a Christian format, the altarpiece. The painting is laid out as a traditional German altarpiece, a triptych with a predella panel beneath. On the left, soldiers march in a smokey dawn. In the center is battlefield carnage. And on the left, weary shell-shocked soldiers return from the front. On the predella panel below, dead soldiers rest as if in the grave.

Dix was one of many artists to return to more traditional figurative painting after the War. The distortions of Expressionism and the break up of form by Cubism appeared unseemly after real human bodies were disfigured and broken up by new high power weaponry.

A full sized drawing for Metropolis by Dix.

Dix returned to the triptych format again in Metropolis, 1926 - 1927. This time, Dix vents his fury at what he saw as a corrupt parasitic post War Berlin. Those who profited from the suffering of millions of people landed on their feet after the War and got even richer from the economic collapse at the end of the War. Those who became rich from burdens borne by others celebrated while crippled veterans begged in the streets. Most veterans like Dix shared this view of Weimar era Berlin; economic parasites profiting from the poverty and suffering of the men who fought. Many of those veterans became attracted to political extremism. Dix became a card-carrying Communist. Most of the rest of his comrades would eventually find their way into the Nazi party.

|

Otto Dix's famous portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden from 1928.

This painting sums up the sophisticated free-spirited cosmopolitan culture of Weimar era Berlin for many people complete with the monocle and the tobacco stained teeth.

Conrad Felixmüller's painting of the suicide of the poet Walther Rheiner from 1925 also summarizes the very edgy demimonde of Weimar Berlin. Rheiner was a literary nomad of a kind familiar in our own day, living by the week from sofa to sofa, cafe to cafe. Felixmüller illustrated selections of Rheiner's poetry. Rheiner suffered from worsening addictions to cocaine and morphine finally driving him to suicide at the age of 30. So many of his poems were about the experiences of drug addiction.

I've always been fond of this painting made soon after Rheiner's death. The poet leaps over the geraniums on the window sill into the night drawing a lace curtain over the moon. The painting of nighttime Berlin in the background is magical with a kind of heightened hallucinatory intensity perhaps suggesting a drug induced euphoria.

Another painter of the Weimar era Berlin demimonde was Christian Schad. Schad enjoyed little commercial success or recognition in his lifetime. That obscurity apparently protected him from Nazi scrutiny after 1933. His father, a wealthy attorney, supported Schad until the stock market crash of 1929. Schad's work went through many phases. He started out as a Cubist painter. As a pacifist, he opposed German participation in World War I and sat out the war in Zurich where he met the poets and artists of Dada and became a Dada artist himself. Schad mostly stopped painting after 1933, taking it up again only after the end of World War II. Today, he is most famous for his figurative paintings from the 1920s.

Schad was part of a loose movement of figurative artists in Berlin (including Dix) called Neu Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity.

Christian Schad, Sonja, 1928

Christian Schad, Graf St. Genois d'Anneaucourt, 1927

The Count St. Genois d'Anneaucourt was a minor aristocrat on the Berlin party circuit in the 1920s. Schad portrays him at a Berlin rooftop party with a woman on the left and a transvestite on the right.

Christian Schad, Self Portrait, 1927

Here is Schad's strikingly sexual self portrait with a woman wearing a scar on her cheek.

Of all the angry artists that worked in Weimar era Berlin, few were angrier than George Grosz. Born Georg Gross in Berlin to a devoutly Lutheran family of tavern keepers, he changed his name to protest German nationalism and militarism.

George Grosz, The Funeral (Dedicated to Oskar Panizza), 1917-1918

Grosz painted this turbulent cityscape in the last years of the First World War and on the eve of the Spartakus Uprising. It shows a chaotic funeral procession at night through a modern city (perhaps Berlin). Like other early 20th century German artists, Grosz draws upon German medieval art; in this case, hell scenes and the Dance of Death. Grosz uses aspects of Cubism (without the Cubist break up of form) to create a dizzying sharp perspective of a narrow avenue through teetering buildings. The whole painting glows with an infernal red light. The Grim Reaper sits upon the coffin drinking while rioting breaks out all around.

Far from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's sharp edged and nervous pleasure in the women displaying themselves on Berlin's busy streets, Grosz regards the crowded chaotic city with all the horror of a son of pious parents (which he was). The city remains in Grosz's vision the place of dissipation where identity and purpose dissolve in temptation and disorder.

Oskar Panizza was a psychiatrist and an avant-garde poet and playwright popular with younger artists and writers of Grosz's generation. Panizza is best remembered for his play Das Liebeskonzil (The Love Council) based on the first documented outbreak of syphilis in 1495 and set in heaven and hell. God the Father appears as a senile old man while a slutty Virgin Mary negotiates with Satan for a poison the will rot sinners from the inside out while leaving them capable of asking for salvation.

Panizza was arrested, tried, and sentenced to a year in prison for blasphemy over this play.

George Grosz had his own encounters with the law over the course of his career. Grosz watched officers destroy a suite of drawings under court order after he was convicted of blasphemy.

While Grosz's military experience was very limited, -- recruitment officers rejected his enlistment in 1914 over his poor health -- he fully shared Otto Dix's fury at the parasitic corruption he saw flourishing at the end of the War. He brought to that fury an almost religious moralizing anger.

George Grosz, "Daum" Marries Her Pedantic Automaton "George" in May 1920 (John Heartfield is Very Glad of It), watercolor and collage, 1920

Few 20th century artists attacked prostitution with more righteous zeal than George Grosz. For a true believing Communist like Grosz in 1920, the whore was the ultimate sell out to capitalism and militarism. Here, the unseen forces of state power persuade a prostitute to marry a good citizen portrayed as a mindless robot with mechanical parts who is hungry or aroused when told. A disembodied hand arouses "Daum" while other disembodied hands feed thoughts into "George's" empty head. Grosz shows what he insists is the real nature of marriage in so corrupt a society. Only a mindless robot would willingly support such a parasitic regime, and the only woman possible for such an empty suit is a prostitute.

George Grosz, Pillars of Society, 1926

In this painting, Grosz makes quite clear his feelings about an unholy alliance between capital, militarism, and official religion. No one will ever accuse Grosz of an excess of subtlety. His work has the screaming high contrast moral clarity of a popular religious tract. The fat hypocritical pastor with his unctuous preaching, the wealthy bourgeois clinging to his imperial German flag with shit for brains in his open head, the crazed military nobleman in the foreground with his open empty head full of phantoms of military glory, and behind him another solid citizen wears a chamber pot for a helmet while carrying the palm of victory; all of these are not people but types, the types Grosz saw through his moralizing spectacles in the beer garden and on the street.

For all of his flag-waving leftist politics, Grosz remained the son of pious parents, as simple minded in his moralizing as they ever were. Grosz simply traded in one moralizing eschatology for another when he left Christianity for Marxism.

For all of his flag-waving leftist politics, Grosz remained the son of pious parents, as simple minded in his moralizing as they ever were. Grosz simply traded in one moralizing eschatology for another when he left Christianity for Marxism.

Grosz quit the German Communist Party after spending six days in the Soviet Union where met Lenin. Grosz was not impressed. He kept his far left Marxist views, views that forced him to leave Germany for the USA in 1938 after the Nazis made life impossible for him. Grosz spent most of the rest of his life teaching at the Art Students' League in New York City (Romare Bearden was one of his students). In 1959, he returned to Berlin to retire, and died there after falling down stairs in the same year.

Max Beckmann in Berlin

Max Beckmann gets thrown together with the New Objectivity painters in the textbooks, but really, he is in a category all by himself. He spent only 4 years in Berlin, 1933 - 1937. He finished his most famous painting, The Departure, there in 1935. He began it in Frankfurt in 1932 and continued working on it after his move to Berlin.

When Beckmann arrived in Berlin with the unfinished Departure, his career was in a rapid downward spiral. The Nazi government fired from his teaching position at the Staedel Institute in Frankfurt. Major museums and public collections removed his work from their walls. In less than a year, Beckmann went from being among the most celebrated of living German artists -- the close friend of critics, major collectors, and museum curators -- to a national pariah. Although Beckmann always denied that there was any political content in Departure, his recent misfortunes at the hands of Germany's Nazi regime almost certainly inform this work. The Departure also seems to eerily anticipate Beckmann's own hurried departure from Germany in 1937 after the Degenerate Art Exhibition prominently featured his work. He suddenly left behind his home and studio for Amsterdam where he waited for permission to emigrate to the USA. The German Army invaded Holland just as his visas came though. Beckmann spent the war years hiding in an attic in Amsterdam (not far from Anne Frank's hiding place) protected by a sympathetic SS officer who shielded him from detection and arrest and kept him in art supplies.

When Beckmann arrived in Berlin with the unfinished Departure, his career was in a rapid downward spiral. The Nazi government fired from his teaching position at the Staedel Institute in Frankfurt. Major museums and public collections removed his work from their walls. In less than a year, Beckmann went from being among the most celebrated of living German artists -- the close friend of critics, major collectors, and museum curators -- to a national pariah. Although Beckmann always denied that there was any political content in Departure, his recent misfortunes at the hands of Germany's Nazi regime almost certainly inform this work. The Departure also seems to eerily anticipate Beckmann's own hurried departure from Germany in 1937 after the Degenerate Art Exhibition prominently featured his work. He suddenly left behind his home and studio for Amsterdam where he waited for permission to emigrate to the USA. The German Army invaded Holland just as his visas came though. Beckmann spent the war years hiding in an attic in Amsterdam (not far from Anne Frank's hiding place) protected by a sympathetic SS officer who shielded him from detection and arrest and kept him in art supplies.

The Departure is a triptych, the first of many more that Beckmann would make to the end of his life. As in the work of Otto Dix, Beckmann uses a medieval religious format to communicate and universalize reflections on his own experiences. Like medieval art, Beckmann's work is full of what appears to be allegorical symbolism. Beckmann insisted that all these images did not have single specific meanings and brusquely rebuffed any questions about interpretation. And yet, this painting like so much of his later work, seems to demand just that kind of iconographic explanation that Beckmann refused to give. The two side wings appear to be set in a hotel or the corridors of a theater. Dark browns and blacks dominate the unstable and claustrophobic spaces. Absurd and violent incidents take place in these close vertiginous spaces. In the center panel, a group of figures in mythological dress appear to be setting out on a boat for the wide open horizon of the sea. This panel is as bright and expansive as the others are dark and close. A figure wearing a crown with his back to us appears to be releasing fish from a net. Another masked figure to the left steers the boat. In the very center of the whole triptych is a woman holding a child. The child has his back to us and occupies the exact center of the composition. He seems to be looking past another half hidden figure toward the open sea beyond. Bright reds, yellows, and blues dominate this picture. The blue of the sky covers an underpainting of red that only enhances the blue color's brilliance. Most of the figures in the side panels appear to be inhabitants of the 20th century by their clothes (there is a hotel bell hop in the right panel). In contrast, the figures in the center wear the costumes of figures in great mythological dramas.

Below are my photographs from 2013 of the Departure in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Otto Dix's triptychs and George Grosz's paintings express rage and protest at the corrupt new world that rose out of the ashes of World War I. Max Beckmann wanted to look deeper beyond the politics of the moment into why such catastrophes happen in the first place. Beckmann's experience of the War was not nearly as extensive as Dix's, but it was very horrific even if it was brief. Beckmann worked as a medical orderly retrieving the wounded from the battlefield, and more frequently, picking up the pieces of the dead and returning them to make-shift battlefront morgues. Beckmann lasted about a month in this work before he had a breakdown and was invalided out of the army. Instead of occupying himself with the politics of the moment, Beckmann asked deeper questions about why human beings do such violence against each other in the first place. Why is it that evil flourishes in the world? Beckmann turned inward to the realm articulated by myth and legend. His paintings took on the heavy black lines of early medieval woodcut prints, and the crowded spaces and lumpen proportions of early carved wooden altarpieces. Beckmann took the heavy black outlines of those old medieval woodcuts and turned them into a remarkable back and forth between darkness and light and brilliant color. Not even Rouault played black outlines and darkness off of bright color with the painterly subtlety of Beckmann's work after 1932.

As did Käthe Kollwitz and Otto Dix, Beckmann turned to the forms of earlier religious art to articulate and make sense of his experiences. Beckmann found what he was looking for not in Christianity or Communism, but in ancient Gnostic and NeoPlatonic philosophies. Like those schools of philosophy, Beckmann saw the world as but a prison for the soul made by an evil creator. The whole point of life was to see through the illusions and absurdities and to find the spiritual escape hatch out. Beckmann's own ordeals were hardly over in 1920 when he wrote:

As did Käthe Kollwitz and Otto Dix, Beckmann turned to the forms of earlier religious art to articulate and make sense of his experiences. Beckmann found what he was looking for not in Christianity or Communism, but in ancient Gnostic and NeoPlatonic philosophies. Like those schools of philosophy, Beckmann saw the world as but a prison for the soul made by an evil creator. The whole point of life was to see through the illusions and absurdities and to find the spiritual escape hatch out. Beckmann's own ordeals were hardly over in 1920 when he wrote:

“It is all over with humility before God. My religion is pride before God, defiance of God. Defiance because he created us such that we cannot love each other. In my paintings, I blame God for everything He did wrong.”

Max Beckmann, The King, 1933 - 1937

I knew this painting well when I lived in Saint Louis. It is a modified self portrait with Beckmann's wife Mathilde clinging to his arm on the left. Behind is a mysterious veiled figure in shadow, perhaps some keeper of secret knowledge. Beckmann shows himself crowned as the commanding hero in his quest to survive and escape history. Shadow and black fill this painting giving in grandeur and a sense of foreboding.

***

"Torn Apart By the Explosions of Last Week;"

Dada in Berlin

"Torn Apart By the Explosions of Last Week;"

Dada in Berlin

Dada arrived in Berlin from Zurich with a riot. Richard Huelsenbeck, a poet and veteran of the legendary and short lived Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich arrived in Berlin in 1917. In 1918, he brought the standard Dada fare of public readings of nonsense poems, but with an added twist. He would launch into tirades against the Expressionists, against particular artists, against the German government and military all in an effort to provoke the audience. Huelsenbeck allegedly disrupted an opening of an exhibition of Lovis Corinth's work by loudly reading his nonsense poems and then insulting Corinth and the other guests. In the riot that followed, there was remarkably no damage to any of Corinth's paintings, though there were some arrests and minor injuries.

Dada in Zurich was a group of social drop-outs, military deserters, and assorted misfits who decided to sit it out while Europe committed suicide on the battlefields of World War One. They wanted to begin art and culture all over again by going back to what they saw as the beginning of all creativity in child's play and the unconscious. They wanted to discard the whole rationalist materialist world view of late 19th century Europe that they blamed for the War. Rationality and sense led ultimately to battlefield slaughterhouses like Verdun and Ypres, and to the lies told to justify that slaughter. The Dada group in Zurich embraced nonsense as a positive value. They adapted a childish nonsense word "dada" as the name of their group. Instead of "acting their age," they embraced the fresh unprejudiced innocent imagination of childhood. They were a short-lived group of hippies creating another alternative counter-culture.

Berlin Dada was revolutionary and out to destroy the old order. There weren't interested in creating any alternatives. They were out to destroy the military capitalist order that they blamed for the War and that they believed ruled a corrupt Weimar Republics still born out of surrender. All of them were card carrying Communists (though the party rightly suspected them; in their heart of hearts the Dada artists in Berlin were less loyal obedient soldiers of the Party than radical anarchists). Dada artists in Berlin positively reveled in the violence and chaos that swept Berlin at the end of the War during and after the Spartakus Uprising. This embrace of modern chaos and transformation comes through in the angry manifesto Richard Huelsenbeck wrote for the movement in 1918:

The execution and direction of art depends on the times in which it lives, and artists are creatures of their epoch. The highest art will be that whose mental content represents the thousandfold problems of the day, which has manifestly allowed itself to be torn apart by the explosions of last week, and which is forever trying to gather up its limbs after the impact of yesterday. The best and most unprecedented artists will be those who continuously snatch the tatters of their bodies out of the chaos of life's cataracts, clutching the intellectual zeitgeist and bleeding from hands and hearts.Has Expressionism fulfilled our expectations of such an art, one which represents our most vital concerns?No! No! No!

Have the Expressionists fulfilled our expectations of an art that brands the essence of life into our flesh?No! No! No!

Under the pretext of inwardness the Expressionist writers and painters have closed ranks to form a generation which is already expectantly looking forward to an honourable appraisal in the histories of art and literature and is aspiring to honours and accolades. On the pretext of propagating the soul, their struggle with Naturalism has led them back to those abstract, pathetic gestures which are dependent on a cosy, motionless life void of all content. Their stages are cluttered with every manner of kings, poets and Faustian characters, and a theoretical, melioristic understanding of life — whose childish and psychologically naïve style will have to wait for Expressionism's critical afterword — lurking at the backs of their idle minds. Hatred of the press, hatred of advertising, hatred of sensationalism, these indicate people who find their armchairs more important than the din of the streets, and who make it a point of pride to be conned by every petty racketeer. Their sentimental opposition to the times, no better nor worse, no more reactionary nor revolutionary than any other, that feeble resistance with half an eye on prayer and incense when not making papier maché cannon balls from Attic iambics — these are the characteristics of a younger generation which has never known how to be young. Expressionism, which was discovered abroad and has quite typically become a portly idyll in Germany with the expectation of a good pension, has nothing more to do with the aspirations of active people. The signatories of this manifesto have banded together under the battle cry ofDADA !!!!

The Dada artists made their public debut with the First International Dada Fair of 1920 held in a small gallery in Berlin from June to August of that year.

The First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920: Raoul Hausmann stands on the left in a cap, Hannah Höch sits on the left, George Grosz stands on the right with a cane, behind him on the far right is John Heartfield. This "exhibition and sale" took place in a small gallery owned by Dr. Otto Burchard (seen standing on the left behind Hannah Höch and talking to Raoul Hausmann in the photo), an expert in Song Dynasty Chinese ceramics who underwrote the exhibition.

"Take Dada seriously!" says the sign on the upper left wall, "it's worth it!" In what will become a pattern down to the present day, this newer generation of post-War survivors mercilessly turned on the preceding youth movement represented by the Expressionists. These artists did indeed make art out of the limbs gathered up from last week's explosion. They rejected traditional painting and sculpture to make art out of the discarded detritus of urban modernity itself. The Berlin Dada made collages and montages out of photos and illustrations from popular magazines, news and political journals, and textbooks.

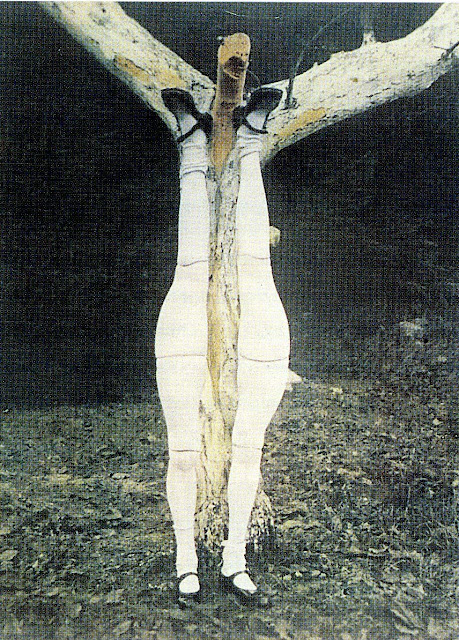

The Berlin Dada artists also made sculptures by assembling together bits and pieces of Berlin modernity. One of them appears in the photo above, a mannequin hanging from the ceiling dressed in a German military uniform with the head of a pig. They made many such sculptures, but only one survives, Raoul Hausmann's Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time) from 1919 - 1920.

It is a mass produced wig maker's dummy with a ruler, pocket watch, a wallet, parts of a camera, and a funnel attached to it. It is a sculptural version of George Grosz's "George," the good German citizen as mindless automaton given measuring instruments for finding his way, and a funnel in the top of his empty head ready to receive whatever the rulers decide to pour into it.

It is also a deeply pessimistic vision of modern humanity. The individual is a passive and helpless creature of larger forces and power structures that shape it. The individual's sense of self and individual free will and agency ultimately are but an illusion, that in fact he is a non-entity, a helpless nothing that is but flotsam floating aimlessly in the currents and countercurrents of power and history.

A sample of Hausmann's collage work from 1920 to 1923:

Raoul Hausmann, Self Portrait of the Dadasoph, 1920

Raoul Hausmann, Dada Siegt! (Dada Wins!), 1920

Raoul Hausmann, ABCD, 1923; a modified self-portrait incorporating a photograph of his own face and parts of an advertisement for a performance of some of his nonsense poetry. Also included is a single Deutsch Mark note and a very sexually suggestive medical illustration of a gynecological examination. This was his last photocollage.

Hausmann abandoned collage for photography, and surprisingly conventional photography of nudes and scenery. He led a notorious sex life preferring menage a trois over monogamy. Some women were willing. Others certainly were not. With the Nazis rise to power, Hausmann left Germany for Ibiza in Spain in 1933 with his Jewish wife and his Jewish mistress. The Spanish Civil War beginning in 1936 forced them to leave again, first for Zürich, then Prague, and then Paris. They lived together in rural France keeping as low a profile as possible during the German occupation until 1944. Hausmann survived the war and died in 1972.

More than any of the other Berlin Dada artists, John Heartfield put his work before the public eye.

Here is a photo from 1928 showing passers-by in Berlin looking at an election poster for the German Communist Party designed by Heartfield, The Hand Has Five Fingers...

Heartfield made work for mass reproduction on posters and in left wing publications. He is most famous for his ferocious attacks on Hitler from 1930 to 1938.

In 1933 when the Nazis came to power, the Gestapo broke down the door of Heartfield's Berlin apartment just as he leapt from a back window. He hid for days in a garbage bin, and then fled on foot across the Czech border to Prague. It was from the relative safety of Prague that he made these posters that show up on German walls to the intense annoyance of the Nazi regime.

John Heartfield, "Don't Worry. He's a Vegetarian," 1936

John Heartfield, "This is the Medicine That They Bring!" 1938

John Heartfield, Blood and Iron, 1934

John Heartfield was born Helmut Herzfeld in Berlin. When he was but a small child, his parents abandoned him, his brother and two sisters in the woods. An uncle rescued and raised the children.

Like so many German young men, Heartfield enthusiastically joined the army in August 1914 and was accepted despite his short stature (5 feet 2 inches). By 1916, he became very disillusioned with the war, and anglicized his name in protest of the German government's anti-English policies. Heartfield joined the Communist Party after the Great War.

In 1938, the Gestapo paid Heartfield the great compliment of placing him at number 5 on their Most Wanted list. When the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia in 1938, Heartfield escaped to Britain where he remained for the duration of the War. At the end of the War, the British denied his application for citizenship and he returned to East Germany where he was monitored and frequently bullied by the Stasi while being publicly acclaimed as a Hero of the People until his death in 1968.

The best of all the photo and magazine collagists of the Berlin Dada movement was Hannah Höch in my opinion. Her collages from the 1920s still have a resonance and disturbing quality over 90 years later. In her lifetime, Höch was mostly known as Raoul Hausmann's mistress (he was still married at the time). Other Dada artists such as Hans Richter, remembered her for her 'contribution;' "sandwiches, beer, and coffee that she managed to conjure up despite the shortage of money."

While publicly paying lip service to female emancipation, Dada included relatively few women artists and poets among its ranks. Hannah Höch set out to expose that hypocrisy and to challenge the popular idea of the "New Weimar Woman," a figure who would seem familiar in our own day. The New Weimar Woman was a career woman who rejected the traditional roles of mother and housewife. This concept prevailed at the same time that 19th century concepts of the mother as bound to the house and responsible for raising children remained very common and articles of faith in most public opinion. Despite their public declarations of feminist solidarity, Dada men (in a way similar to men of the New Left of the 1960s) still thought of their women comrades as concubines and household servants.

Höch was one of those working New Weimar Women. She worked for popular women's magazines and for news magazines. The photo imagery of that popular press formed the source and the materials of her art.

Hanah Höch made her debut as an artist in 1919 with this large collage with the remarkably evocative title of Cut With the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Beer Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany. This collage is filled with famous people of the day: Albert Einstein, Kaiser Wilhelm, Käthe Kollwitz, Field Marshall von Hindenburg, Karl Liebknecht, and others. Raoul Hausmann is among them. She recombines heads and bodies. For example, Höch puts the head of von Hindenburg on the body of a famous dancer of the day, Sent M'ahesa. This cutting apart and recombining genders and gender roles will be the subject of a lot of her work.

It is a picture perhaps best appreciated in its details.

She made this collage DaDandy in 1919 to call out the hypocrisy of the Dada men when it came to women. Höch cut into photographed faces and sliced them apart and remade them in a way that reminds me of what Picasso would do with his mistresses in his paintings of the 1930s. But Höch cuts directly into a photographed image, not remaking a likeness as in a painting. She seems to be playing a kind of Dr. Frankenstein role making new beings out of body parts, new faces out of the assembled pieces of others.

So many of her collages like this one recombine masculine and feminine roles and imagery in ways that are unexpected and very memorable. Here a photo of the head of a female mannequin is grafted on the muscular body of a man showing off his muscles. The image appears through what appears to be a tear in a panel of studded leather.

Höch worked for popular women's magazines and knew quite a lot about how marketing deliberately shapes the desires and ambitions of consumers, especially young women. In this striking collage, she pulls apart and then reassembles photographs of fashionable women into something that looks scarred and monstrous.

Some of Höch's most striking images are from a series of 20 collages from a series "From An Ethnographic Museum" that she made from roughly 1920 to 1930. She combines parts on African and Asian sculpture with living female body parts, an unusual and prescient comment on racial identity. These prints are remarkably inventive and some of her best work.

I don't think anyone wielded scissors or a cutting knife with such freedom and skill as Hannah Höch.

Hanah Höch's relationship with Raoul Hausmann gets routinely described as "stormy" and it certainly was. It even became violent at times. His somewhat childish sexual needs ran into her demand that he divorce his wife. She called Hausmann out on his own hypocrisy frequently, and sometimes publicly. There was certainly a large measure of rivalry driving both their attraction for one another and their fighting. After 7 years, Höch left Hausmann in 1922. Höch entered into a same sex relationship with the Dutch writer Til Bruggman. Their relationship lasted until 1935.

During the Nazi years, Höch lived on the outskirts of Berlin and kept a very low profile. In 1938, she married Kurt Matthies, a wealthy businessman (possibly for protection) and divorced him in 1944. After the War she resumed her artistic career and lived long enough to see a revival of interest in her work. She died in Berlin in 1978.

The Berlin Dada artists attract a lot of attention these days. Artists like Hannah Höch made art in the 1920s out of a lot of issues that preoccupy us now. For 25 years running here in the USA, these artists are held up as models of artistic "resistance." I think it is fair to ask how effective were they in promoting the social and economic democracy that they stood for. I think it is also fair to ask how well we really understand them and their situation, and how distinct they are from our own circumstances.

About 15 years of Berlin Dada's activity and agitation did little to nothing to stop or even slow down the big Nazi electoral victory in 1932. The fortunes of the German Communist Party slid into catastrophe despite the best efforts of these artists. When the Nazis took power, most of these artists went silent; either into hiding or exile. The only one of them who kept needling the Nazi regime with his work all the way up to 1938 was John Heartfield. But even he eventually fled rather than face the full force of Nazi terror. And who could blame them? The full force of Nazi terror was very terrifying and always fatal. Most of all, they would have been alone. They knew that public opinion in Germany at the time was with Hitler, not with them. As far as the German public was concerned, the Berlin Dada artists were a small group of subversive cranks; irritating social deviants, but no real threat to the regime.

Looking back at the brave and futile artists of the Berlin Dada, we should ask ourselves what we mean by an art of "resistance" now at a time when the USA is itself in a kind of existential crisis, and liberal democracy appears to be in rapid retreat around the world. What do we want that art to do? Do we expect it to play some kind of active role in regime change? Do we want it to perform a kind of propaganda function? Or do we want it to do something else? That's the problem with art. It is fundamentally useless from a purely utilitarian or actuarial viewpoint. It is not much of a means to any end. We regard art that does function as a means with justifiable suspicion; as advertising or propaganda. We expect, we even demand, that art must simply be itself in order to speak authentically to us.

Politically useful or not, the art of the Berlin Dada at its best remains powerfully authentic from an increasingly distant past. Hannah Höch's collages have lost none of their disturbing visionary power. John Heartfield's posters remain very punchy aggressive memorable messages. Will anything like that from our day endure as well over time? Does that question even matter since the shape of that future is the very bone of contention now?

I've been very disappointed over the last 25 years or so to see so much political art embrace the forms and aesthetic of probably the most arcane and uncommunicative art genre ever created, 1970s Conceptualism. Political art if anything should be communicative. All of these artists in Berlin understood that, especially John Heartfield. A semiotics seminar at the New School is just not going to reach much of anyone. A swastika made of bloody axes or a collage of General Hindenburg's head on the body of an exotic dancer will. I wonder if the people who gaze upon this work with so much admiration and romanticize about courageous resistance in Weimar Berlin understand that aspect of their work.

***

Surrealism in Berlin

Surrealism in many ways was the last great Romantic movement in art, a movement dedicated to throwing off the last restraints on the instinctual, on passion, long regarded as the truest sources of inspiration. Surrealism took the anti-rationalist protest of the original Dada movement much further. The Surrealists aimed to subvert ordinary comprehensible reality, and to turn it into a portal to what they called "the marvelous." The autocratic and puritanical leader of this movement was the poet and physician Andre Breton. Among the earliest artists inducted into the movement by Breton was Max Ernst, formerly a Dada collage artist working out of Cologne. Ernst was Germany's greatest Surrealist and among the greatest of all the Surrealist artists (and my personal favorite of the group). But, Ernst spent most of his working life in Paris and later in the USA and so is outside the scope of this post.Surrealism in Berlin

Perhaps I will do a separate post on him at a later date. In the meantime, here is a small sample of his richly poetic and multifaceted work.

Max Ernst, The Entire City, 1936

Another Surrealist who worked in Berlin and made very disturbing photographs based on a hinged doll hand made of plaster was Hans Bellmer. In 1934 after Hitler had come to power, he published anonymously a suite of 10 black and white photographs titled Die Puppe (The Doll). They are photographs of a plaster and wood doll with ball hinges that Bellmer built himself. The clothes indicate that the Doll is supposed to be a stand in for an under-age girl. Bellmer photographed the Doll in a series of disturbing scenarios that suggest both pornography and crime scene photography. Some of these photographs he colored by hand in bright lurid colors.

Bellmer later claimed that he intended these photos to be a protest against the Nazi cult of the healthy athletic body. Maybe. What they clearly show is a set of fetishistic images strongly suggesting the sexual violation of a young girl, willing or not. They are very disturbing and haunting without being explicit. He published these privately and anonymously. These photographs were almost entirely unknown in Germany, but were widely circulated in France in Surrealist journals such as Minotaure. Bellmer eventually fled Germany for France in 1938 where he spent the Nazi occupation in hiding, and the rest of his life afterward. In his later years he made erotically charged prints and drawings, and took erotic photographs of models who were definitely too young.

The Surrealists plumbed the depths of the unconscious in the name of absolute liberty, including the liberation of instincts that lead to what most of the rest of us would call crime. I look at Bellmer's photographs with a certain measure of admiration for their daring and for their still disquieting power after more than 80 years. At the same time, I cannot help but remember that Freud thought very little of the Surrealists and considered them all to be frauds. Freud used work like this to argue that indeed, repression is a good and necessary thing.

Instincts of terror and hatred far darker and stronger than anything explored by the Surrealists swarmed out of the collective European subconscious that Hitler opened up. The Nazi years were a Roman holiday for psychopaths and sociopaths all over the continent creating scenes of horrific violence far darker than anything Bellmer could dream up.

A photograph taken somewhere in Eastern Europe in the 1940s by an anonymous German soldier. It shows the aftermath of a small massacre of picnickers with the corpse of a girl on the table who appears to have been raped. We can see the soldiers in the background returning to their train.

From the Daniel Menchner collection of wartime photographs.

Friday, March 17, 2017

Artists' Berlin 2

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Brandenburg Gate, 1915

Lovis Corinth and Käthe Kollwitz

Lovis Corinth, Self Portrait with Straw Hat, 1923

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait, 1925

A painter who pointed a way forward for aspiring artists, who created an alternative to both the obedient civil service represented by Von Werner, and the imitation of French painting championed by Max Liebermann and the Berlin Secession was Lovis Corinth. Corinth was originally from East Prussia and studied painting in Munich. But he had his debut exhibition in Berlin in 1899 with the Berlin Secession. He later moved to Berlin and exhibited regularly at Paul Cassirer's gallery. Artists saw him as a liberating figure. Corinth took French Impressionism to an emotional fever pitch that artists like Monet and Pissarro never intended. Corinth painted very un-Impressionist subject matter from myth and religion that appealed to German sensibilities.

Lovis Corinth, The Walchensee Serpentine, 1920

Lovis Corinth, Flowers, 1920

Lovis Corinth, The Slaughterhouse, 1893

Lovis Corinth, Blinded Samson, 1912

Lovis Corinth, Red Christ, 1922

Corinth did not love them back. He kept his distance from the younger moderns frequently attacking their work.

***

Another artist who pointed a way forward for German artists was the great graphic artist and sculptor Käthe Kollwitz. She remade the great themes of Christian religious imagery that always dominated German art since the earliest middle ages and still resonated deeply with artists and public alike in the early 20th century. Kollwitz secularized and updated a lot of traditional religious imagery and gave it a new emotional force. While her secularized Madonnas and Pietas lost their traditional religious meanings, they gained a new powerful empathetic appeal.

Käthe Kollwitz had a long and dramatic life deeply touched by left wing Christianity. Her father was a mason and house builder whose political sympathies were radically social democratic. Her grandfather was a Lutheran pastor expelled from the official Evangelical State Church of Prussia for his socialist views. Her husband Karl was a medical doctor who tended the poor in Berlin. Their house was next to the clinic where he worked. The patients at the clinic inspired much of her work.

Käthe Kollwitz was the first woman admitted into the Prussian Academy of Arts, though her gender limited her opportunities for art education when she was young.

In the First World War, she lost her younger son Peter in combat. In World War II, she lost her grandson, also named Peter. Her husband died in 1940 from illness.

During the Nazi regime, she was forbidden to exhibit and all of her work was removed from museums and other public collections. The gestapo threatened her and her family with deportation to a concentration camp. She received numerous offers to move to the USA, but refused them all fearing reprisals on her family.

In 1945, the Allied bombing of Berlin destroyed her home and forced her to flee the city. She went first to Nordhausen, and then later to Moritzburg outside of Dresden where she died just 16 days before the War ended.

She was a great master of the print media, especially etching with its lights and darks. She used the tenebrism of etching to great dramatic effect.

Käthe Kollwitz, Death, Woman, and Child, 1910, etching

Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child, 1903, etching

A very powerful print showing a primal almost animal grief over the loss of a child.

Käthe Kollwitz, Man with Dead Wife, 1903

From a series of prints inspired by the Peasants' War of 1524 -1525, probably her best and most powerful print cycle. Sharp contrasts of light and dark, simple concentrated imagery make these major masterpieces of print. Many of them have a dramatic concentration that anticipates cinema.

Kollwitz uses an episode from the distant German past to speak urgently to its present at the beginning of the 20th century.

Käthe Kollwitz, Sharpening the Scythe from The Peasants' War, 1902 - 1908, etching

Käthe Kollwitz, Raped, from The Peasants' War, 1902 - 1908, etching

Käthe Kollwitz, Outbreak from The Peasants War, 1902 - 1908, etching

Käthe Kollwitz, The Prisoners, from The Peasants' War, 1902 - 1908

Käthe Kollwitz, Searching for the Dead from The Peasants War, 1902 - 1908, etching

Käthe Kollwitz, Lamentation: In Memory of Ernst Barlach, 1938

Käthe Kollwitz remade Christian subject matter in her sculptures too, and perhaps with even more concentration. This memorial that she made for her friend and mentor, the sculptor Ernst Barlach shows a simple fragment of her own grieving face held by her hands.

Käthe Kollwitz, Mother With Dead Son, 1937

Probably her most famous variation on the Pieta subject, this sculpture now forms the centerpiece of a remade war memorial in the Neue Wache in Berlin. Since 1931, this former guardhouse served as a war memorial, first to the military dead of World War I, then in 1970 as a memorial to the "Victims of Fascism and Militarism" during the DDR. In 1993, the German government remade the Neue Wache into a memorial for all the civilian dead of World War II and made this sculpture by Kollwitz as its centerpiece. It sits under the open sky though an oculus in the ceiling in all weather.

Käthe Kollwitz's prints and sculptures demonstrate very forcefully the continuing communicative power of imagery. Seeing a reconstruction of our own experiences of the world, both in terms of our senses, and our emotions, still has an unsurpassed empathetic appeal. This remains true even in our age saturated with vivid imagery created by technology. While her politics may have been far left, her art is a conservative triumph. Kollwitz understood that the distortions of form created by Expressionism, and the Cubist break up of form create emotional distance. A self-consciousness about form inserts itself between the vision and us. Of course, form was always there between us and the subject, but in Renaissance and Baroque art, form makes itself invisible as it plays its part in conjuring up a vividly real looking apparition before our eyes. That self-consciousness about form begins to insert itself beginning with Cezanne's work. It could be argued that Cezanne and his legacy were necessary correctives to an illusionistic art that lost its contact with experience and with what is real and true. Kollwitz would probably agree with such a criticism of figurative art. But, she believed that she had more urgent matters of human need and justice to be served. She lived most of her life amid human misery. She ended her days under threat and in the midst of warfare and on the run. The project to close the gap between form and subject was something that she could not afford, nor could her audience have such a luxury. She wanted her art to stir feeling above all else. And what better way to do that than through appealing to our experiences of the world as vividly and memorably as possible.

There is a certain reluctance in much of German modernism to break up form out of the fear of emotional distancing. Die Brücke painters really stretch form, but they never quite break it. We see that reluctance to break apart imagery in Max Beckmann's work, in the work of Otto Dix, Christian Schad, and eventually in Anselm Kiefer's work. If we want to see a radical departure form imagery entirely, we have to go to Munich and see the work of the Blue Rider artists. But even Kandinsky at his most abstract aspired to connect with people emotionally. And that great master of graphic invention Paul Klee still wants to tell stories as memorably as possible

***

Die Brücke Comes to Berlin

Twentieth Century modernism arrived in Berlin in 1911 with a small band of young painters from Dresden and their friends and lovers. They came to Berlin in search of fame and fortune in a much bigger and more sophisticated city.

In 1905, a group of very young architecture students in Dresden (the average age was 19) got together to form the first modern art movement of the 20th century, Die Brücke, The Bridge; and to publish the first (and shortest) of many artists' manifestos in the first half of the last century. They wanted to do much more than reform art. They wanted to build an entire way of life that was the exact opposite of the deeply repressed suffocating official culture of Wilhelmine Germany. All that the culture of Kaiser Wilhelm II wanted to suppress, Die Brücke wanted to liberate.

The other major expressionist movement (and probably the greater one) was Die Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) that belonged to Munich. The Blue Rider had relatively little contact with Berlin, but a much more international network of contacts from New York to Paris to Moscow.

The leader and best artist of Die Brücke was a high strung young man named Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (seated on the right) came from a very respectable bourgeois family, as did most of the other Die Brücke artists. His father (seated to the left of the artist in this family photo) was a very successful and highly respected industrial chemist.

This is a photo taken in 1912 in Kirchner's studio in Berlin. The naked man dancing and smoking may be Kirchner himself, though he's hard to identify here.

Die Brücke was more than a group of like-minded artists. It was a way of life. Shortly after they organized, the artists took over an abandoned butcher shop in Dresden and lived and worked together along with their lovers, friends, and many hangers-on. In 1911, they moved together to Berlin and set up a similar commune. They shared food, living space, friends, and lovers in a collective dedicated to gratifying all the desires and instincts repressed by conventional society. They not only painted together, but they also made their own furniture and wall hangings. Most of the sculpture, furniture, and wall decorations that Die Brücke artists made survive now only in photographs taken by the artists themselves.

Kirchner and Erna Schilling in a corner of his studio with sculptures, furniture, and textiles made by the artists.

An attic bedroom with sculptures, furniture, and textiles on the beds and walls by Kirchner. Photograph by Kirchner from about 1912.

Their desire to completely remake their surroundings according to their wishes would have a great influence on later modern artists and designers. The idea of a total integration of fine and applied art would help shape the ambitions of the Bauhaus almost twenty years later.

The Die Brücke bohemia, like all bohemias, was a bourgeois creation. These sons of German bourgeois respectability pitted bourgeois virtues of independence and initiative against bourgeois vices of hypocrisy and conformism. They created the 20th century's first of many youth "counter-cultures." Their lives of unapologetic scandal first horrified the general public, but then quickly attracted a growing popular interest.

E.L. Kirchner, The Street, 1913

Berlin and its busy streets affected Kirchner very deeply. Their noise, traffic, and crowds thrilled him with a sense of life force, and also frightened him. That same passion to feel deeply and to connect that drove earlier Romantic artists like Caspar David Friedrich far into the countryside drove Ernst Ludwig Kirchner onto the sidewalks of Berlin.

Berlin's women on the streets fascinated Kirchner. Women dressed up for display and/or seduction in public on the streets. Some of the women in his paintings of Berlin streets are street walkers, prostitutes. Others appear to be women of fashion displaying themselves before an admiring public.

Before Expressionism, art -- even most experimental modern art such as Matisse -- aspired to a kind of calm resolution. All of the parts of a painting were supposed to work in harmony with one another. This sense of fulfillment, of completion and self possession became the goal of art as early as ancient Greece. Kirchner and the other Expressionists valued disruption over calm, noise over quiet, dissonance over harmony. In Kirchner's Berlin street paintings, the ground plane begins to tip up and fill the painting creating a kind of vertigo where figures stand before and not on the ground plane. Chiaroscuro vanishes from his paintings. Sharp slashing brushstrokes of unmixed color on raw canvas become as rough and unresolved as the very street scene that he paints.

The color combinations are jarring instead of harmonious; hot pinks with viridian, blue, black, and white; bright pale yellows with black and turquoise blue; colors that in combination set our teeth on edge.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Women in the Street, 1915

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Street Scene, 1913, pastel

E.L. Kirchner, Street Walker in Red, 1914, pastel

E.L. Kirchner, Two Street Walkers, pastel, 1914

An example of Kirchner's electric and sharp drawing technique. The pencil and chalk strokes are rough and violent. The forms are sharp as broken glass. But these drawings -- Kirchner's work in general -- are never crude, never hesitant.

These street scenes show a kind of anxious joy and exhilaration in the noisy chaos of urban street life. For a young man from the comparatively staid and once beautiful Baroque city of Dresden, Berlin's busy noisy streets must have seemed overwhelmingly dramatic, terrifying, and thrilling. It is the thrill that comes through in Kirchner's Berlin paintings more than the anxiety. That kind of intoxicating communion with the life of urban crowds is closer in spirit to Walt Whitman than to the rapturous mysticism of Novalis. In fact, Kirchner loved Walt Whitman's poetry. He kept a German translation of Leaves of Grass on his nightstand by his bed, and read from it daily.

Die Brücke Exhibition at Fritz Gurlitt Gallery, Berlin, 1912

Die Brücke got a big break with a major exhibition at an important Berlin gallery in 1912. The very established and reputable Gurlitt Gallery showed paintings and sculptures by the group attracting a lot of public and press attention for the first time. A lot of the critical attention was hostile, but not all of it. Some of it was very supportive and sympathetic. Their public following increased dramatically and they found themselves playing the role of celebrities. All of the sculpture that appears in this photo is lost. Very few of the Die Brücke group's sculptures survive.

A couple of other members of Die Brücke and samples of their work that they did in Berlin:

Erich Heckel, Glass Day, 1913

Probably his best painting. A nude figure and some landscape details locate us as sky and lake become crystalline shards.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Houses at Night, 1912

I've always been particularly fond of Schmidt-Rottluff's work for its combination of rich brilliant color with very dramatic distortions of form. These distorted houses glow in the ultramarine blue dark with arbitrary colors.

***

Probably the greatest champion and promoter of Expressionism in Berlin was Herwarth Walden. Born Georg Lewin to a wealthy Jewish family, he changed his name in honor of a favorite book of his, Henry David Thoreau's "Walden."

Walden was himself a gifted painter and poet with many cross-disciplinary interests in music and theater. He published a magazine Der Sturm that promoted the work of Expressionist artists, creating an enthusiastic audience and market for their work; and just as important, he put the disparate Expressionist movements in Berlin, Munich, and Vienna in contact with each other, and in contact with other modernist movements such as Cubism in France and Futurism in Italy.

A 1917 cover of Der Sturm

The Viennese Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka's portrait of Herwarth Walden

The leader of Munich's Blue Rider group, and a pioneer of abstract painting was Wasily Kandinsky, a Russian artist who lived many years in Munich. Walden brought his work to Berlin. Here is his painting Black Lines from 1913.

A performance at Walden's Der Sturm Gallery in Berlin. A painting by the French Cubist Robert Delaunay hangs in the background. Delaunay frequently exhibited in Germany, especially in Munich with The Blue Rider group.

Herwarth Walden established a gallery in Berlin, also called Der Sturm that brought the Berlin public and artists in contact with original works by major modern artists of the day, and put original works by younger German artists before the public. Though Walden frequently featured Die Brücke artists in his magazine, he never exhibited their work in his gallery.

Walden was a very courageous and unfortunate man. He braved the harsh moralizing censorship of Kaiser Wilhelm II's government, and the blasphemy laws that continued in the Weimar Republic. The advent of the Nazis forced him to shut down his enterprises and flee the country in 1932. He went to Russia where Stalin's regime viewed him with great suspicion as a promoter of "bourgeois modernism." Walden died in 1941 in a Soviet prison near Saratov.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)