The Passion of Christ

I've completed the bulk of an intended 20 panel series of the Passion of Christ, the second major Passion series that I've painted. Reproduced are 14 out of those 20 panels, all of the monochrome panels for the series are finished. The remaining 6 panels will show the events of the Resurrection. I've completed 2 of those, and begun a third, but none have been professionally photographed yet. Because of the circumstances of the pandemic, etc., I've paused finishing these remaining panels indefinitely. I fully intend to finish, but the changing context may demand changes in conception for those last panels. I may rethink the last 3 panels.

The pandemic cancelled the premier exhibition for this series at St. Luke in the Fields Episcopal Church in New York for Holy Week in April. A first public display of the originals will have to wait for another time, and perhaps another venue.

And so, here all the finished panels professionally photographed.

All these panels are 26" x 26" square, oil on canvas. The first panels are from 2016, and the last are from 2019. Not reproduced here are 2 panels that I completed earlier in 2020.

Emanuel with Job and Isaiah

Jesus Enters the City

The Last Supper

Jesus Prays Alone

Jesus is Arrested

Jesus Before the Priests

Jesus Before the Magistrate

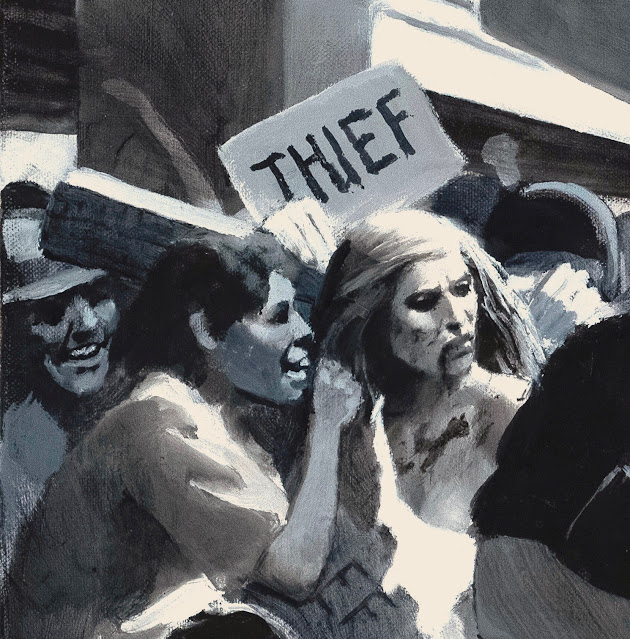

Jesus Before the People

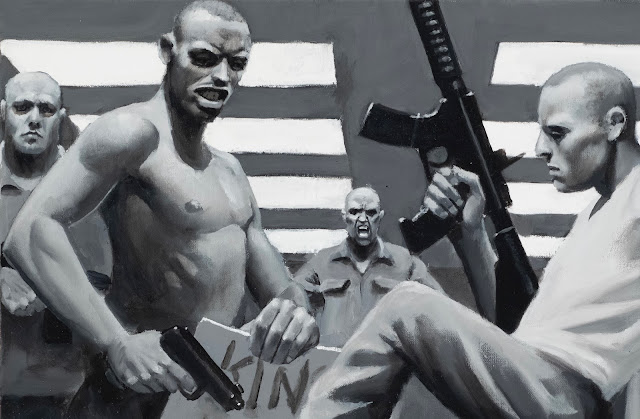

Jesus Before the Soldiers

Jesus is Beaten

Jesus Goes to His Death

Jesus Dies

Jesus is Dead (Lamentation)

Jesus Among the Dead

Below is an essay I wrote for the pandemic cancelled exhibition. It should be noted that I wrote this before the pandemic began.

The New Passion Series: An Essay

Fifteen years ago, I completed a twenty-four panel series of the Passion of Christ after four years of work. That series has since been exhibited, had a book published about it, been covered in the press, and praised by religious and non-religious alike. The originals are now scattered in collections around the world. I owe author Kittredge Cherry a big debt of thanks for putting that Passion series and my art on the map through her splendid writing and continuous advocacy. I also thank the Leslie Lohman Foundation for courageously exhibiting paintings from the unfinished series for the first time, and bringing it to the attention of the public -- and of writers such as Kittredge Cherry. I especially want to thank JHS Gallery in Taos, New Mexico for exhibiting the whole completed series for the first and only time in their great show of contemporary religious art in 2007, “Who Do You Say I Am?” Visions of Christ, Gender, & Justice to mark the publication of Kittredge Cherry’s book Art that Dares.

That first Passion series came out of my experiences with homophobia, the AIDS crisis, and my own religious life. The events of September 11, 2001 that I witnessed from my roof lent urgency to the whole project. That cataclysm added violence and religious fanaticism to the issues I tried to address in that first series.

For a long time, Kittredge Cherry and others urged me to make another series about the Passion of Christ, a suggestion that I resisted. And now that I am older and several years passed since the first series, I embarked on a new Passion series in 2016 that now nears its completion. I decided to make a slightly shorter series, twenty panels instead of twenty four. I painted them on canvas instead of wood panels and made them slightly larger in a square format. I discarded the painted faux frames and the numbering. I decided to paint the bulk of the series in monochrome this time instead of a limited color palette. Some subjects I painted much as I had in the earlier series, and others I made very differently. I’ve now completed sixteen out of the projected twenty panels.

Two big issues drive the changes in this new series. The first comes out of a consistent criticism from the first series, the race of Christ. In that series, I made Jesus white without thinking about it at all. A lot of people pointed out that maybe I should have thought about it, and so I have. In this new series, I made Jesus not white. I did not give him a specific racial or ethnic identity except to make him not white. The historic experiences of non-white people in the white dominated USA inform this new Passion series. I am a gay man, and like the rest of the LGBTQ+ community, I’ve felt directly the experience of being despised and rejected. Too many in the LGBTQ+ community and too many persons of color in the USA walked a literal Via Dolorosa to its fatal end. The second consideration is mortality. I am almost twenty years older than I was when I started painting the first series. As years go by, I feel the losses of so many friends and family more keenly in a world that now feels lonelier. Those issues of mortality and immortality, time and timelessness, death and resurrection at the center of this story have a new resonance for me now. If the new series has a guiding theme, it is that of Emmanuel, God With Us; God in solidarity with us as we suffer misfortune and injustice in the struggles for power that make up mortal life. We all make God in our own image (we can’t help but do so), but I hope that a wide variety of people who are not like me can see themselves and some of their own experiences in Christ in this new series. This new series is darker -- both literally and figuratively -- than the first series. Light and dark play a much more central role in the drama. I made the violence and the malice of the story’s actors much more stark than I did in the first series.

I’m delighted that over the years so many various people found different meanings in the first Passion series. I hope to do the same thing a second time. I’m not making any doctrinal statement clearly spelled out with bullet points in these paintings. I’m making a work of art. That people take what they wish from it and understand it in their own way is fine with me. That’s what works of art do, they provoke thought and reflection. I’ve noticed over the years that my most ferocious detractors among fundamentalists and militant atheists can be very literal minded. The realm of symbol, metaphor, nuance, and suggestion is entirely foreign to an outlook that sees the great wide world through only the narrowest of templates. My work -- or any art other than propaganda -- is not for them.

In both Passion series, I made no attempt to depict the events of the Passion as literal history. I did not want to make any kind of carefully researched reconstruction of events that may or may not have happened in first century Judea. I wasn’t out to reconstruct the past. I was more interested in what the narrative means for now and in every era. I took my inspiration from artists such as Stanley Spencer who set much of his religious subject matter in his native Cookham in England; or from Max Beckmann who so easily combined the mythic with early 20th century urban Germany. I learned from the artists of fifteenth century Europe who regularly set religious stories in settings that looked like their own cities and towns. They saw nothing unusual about setting the Virgin and Child holding court with a group of saints just outside Nuremberg with the city’s walls and spires visible in the background, or on the portico of a Florentine palazzo. Theirs was a different understanding of the past from ours, and literal history did not interest them. What mattered to these artists was what the stories meant in the here and now of 15th century Nuremberg, Florence, or where ever they happened to be.

I wanted to do the same thing in this second Passion series. I wanted to look at a central narrative of Western culture in the light of recent experience. As in the first series, so in this second one I modeled the format on the printed Passion cycles of Albrecht Dürer. Even more so for this second series, I studied the sculpted Passion cycles pioneered in Nuremberg that eventually evolved into the Stations of the Cross. I studied the vivid narrative work of sculptors such as Adam Kraft, Peter Vischer, and Veit Stoss. I wanted to make this series more of a narrative than anything liturgical. I took those formats and added to them the influence of twentieth century photography, especially photojournalism. The monochrome format of fourteen out of the twenty panels recalls that early photography, though in composition they owe more to Renaissance painting and sculpture. I wanted to retain the monumental qualities of that earlier art within a modern context. For the events of the Resurrection in the last six panels, I used a full color palette. I looked at the work of a host of artists for guidance and inspiration including Goya, Rembrandt, Donatello, Giotto, Duccio, Titian, Poussin, William Blake, Holbein, Velazquez, Rogier, Tintoretto, Michelangelo, Pietro Lorenzetti, and Brueghel among others. I also looked to the work of photojournalists such as Margaret Bourke White, Charles Moore, James Karales, Ron Haviv, Robert Capa, Eugene Smith, and many others.

I did not stick too closely to tradition or text in this series. Instead of the Sanhedrin, I painted a council of clerics from just about any religious institution today. Instead of Pontius Pilate, I depicted a law court with magistrates, attorneys, clerks, and bailiffs. Instead of Temple guards and Roman soldiers, I showed well-armed police and military. Instead of Jerusalem, I set the story in what could be New York or any modern city. I wanted the actors, occasions, and settings of the story to be familiar to us, not museum reconstructions of the ancient Roman-occupied Levant.

My own religious convictions inevitably are an issue in this project. I identify as Christian. I am a member of the Episcopal Church and have been for almost forty years. While my political views are left by American standards (LGBTQ rights, labor rights, economic justice, and social democracy among others), my religious views are conservative. I can say the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds without crossing any fingers. And yet, I am a very agnostic believer who doubts openly, but gives God the benefit of those doubts. I believe that if God does exist, and is as the Christian faith says -- human and one of us -- then He lives now and not exclusively in the pages of a Bronze Age book. That person who still lives is the Truth we confess, not a text. The narrative of His life and death rebukes all our measures of glory and success. In the face of that life, death, and resurrection, the whole grim of arithmetic of power and powerlessness forever loses its claim over us. Death is defeated as our final arbiter. As Christ lives, so shall we all live again, and all that is lost will be restored. Christianity is a faith, not a tribal identity. The purpose of being Christian is not to dominate, but to serve. Our duty is to do justice and mercy: to give aid and offer welcome to everyone unconditionally, and to fight injustice, evil, and death -- not other faiths or other people. We must bear witness to the Gospel by doing it freely and faithfully. We must make holy when we’re constantly told that all the world is trash. We must make friends and community when rulers profit from hatred and division. We must be true when language becomes a weapon to coerce and manipulate. We must be humane when violence and cruelty are celebrated. We must love selflessly in a world that never really believed in anything beyond raw self-interest. And we must believe that love is stronger and more final than death.