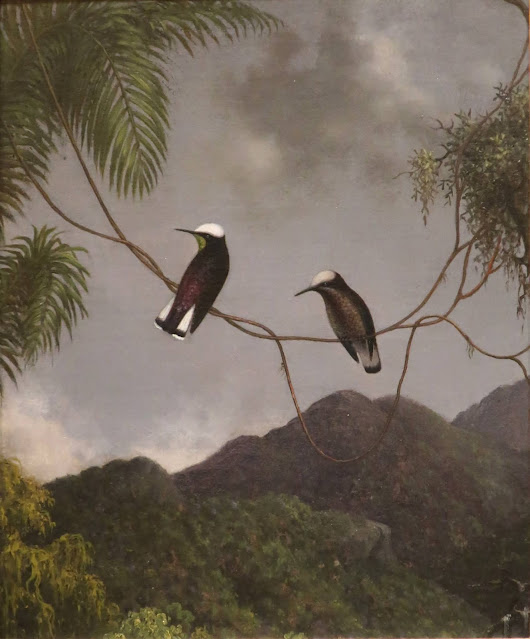

Amethyst Woodstar

In 1863, the American artist Martin Johnson Heade sailed to Brazil to work on a project inspired by John James Audubon's Birds of America. Heade obsessed over hummingbirds, the tiny nectar-feeding birds unique to the Americas with brilliant iridescent plumage. Heade was hardly alone. John Ruskin yearned to see a live hummingbird in flight but he never did. The stuffed species on display in London were all Ruskin saw of the birds. There are no nectar-feeding bird species in Europe. Hummingbirds were an industry in Europe and America, in demand for their brilliant feathers on everything from hats to greeting cards. British hat makers imported tens of thousands of corpses of the tiny birds every year. Heade worried that he would live to see the end of the hummingbirds. Partly out of ambition to rival Audubon's accomplishment, and partly out of love for these tiny amazing birds, Heade spent a year in Brazil's rainforests collecting species and making observations for a magnum opus he planned to title Gems of Brazil, the gems being the hummingbirds. He painted a series of over 40 paintings in Brazil most of them about the same size and format, about twelve inches by ten inches. He intended to have chromolithograph prints made of the paintings and sell them in book format. The enthusiastic reception by the Brazilian public of an exhibition of these paintings in Rio de Janeiro encouraged Heade to pursue publication. The Emperor Dom Pedro II knighted him for his achievement.

The book Gems of Brazil never happened because of Heade's dissatisfaction with the color quality of chomolithography in the mid 19th century, and because of dwindling funds and lack of a sponsor or patron.

Black Breasted Plovercrest

Black Eared Fairy

Black Throated Mango

Among the many bird painters and artistic ornithologists of the 19th century, Heade stands out because of his decision to paint his hummingbirds in their environment with the flowering plants they depended on for sustenance. He shows the moist rainy weather of rain and cloud forests where they live, the daily shifts between sunshine and rain. The birds seem to become natural extensions of the vines and plants they dwell among, as inevitable as the flowers. Heade's paintings still have the sharp silhouetted forms common to a lot of 19th century bird painting including much of Audubon's work. Perhaps the elaborate Victorian taxidermy displays in glass bell jars influenced this format. However Heade shows the environment that these taxidermy displays used to imply.

There is some speculation that Heade may have been aware of Charles Darwin's work on South American orchids and his observation on the close mutual dependence between specific flowers and specific pollinators, especially hummingbirds. Bird and flower evolved together into so exclusive a mutual dependence that the extinction of one would risk the extinction of the other. Perhaps. Heade shows a dependence between bird, flower, and larger environment that is unique for his time, and speaks directly to our time where we are now acutely aware of the tangled web of mutual dependence upon which all life depends including ours.

Brazilian Ruby

Crimson Topaz

Fork-Tailed Woodnymph

As in so much 19th century American painting, there is an imperial subtext to these paintings. Before and during the Civil War there was much talk of extending American imperial ambitions southward to Cuba, Nicaragua, and ultimately South America. The Confederacy was particularly enthusiastic for a South American empire. It's sad to discover that so many early 19th century pioneering ornithologists including the great John James Audubon were Confederate sympathizers.

But the obsessive eccentricity of Martin Johnson Heade's work mitigates some of that chest-thumping imperial ambition. His work seems to me less imperial than Victorian. For example Heade shows a family of Fork-Tailed Woodnymph hummingbirds above with male and female parents tending to their young in the nest below, a model family. In fact, the male hummingbird usually plays no role in nest building or chick raising.

Frilled Coquette

Hooded Visorbearer

Ruby Throated Hummingbird

Ruby Topaz

Snowcap

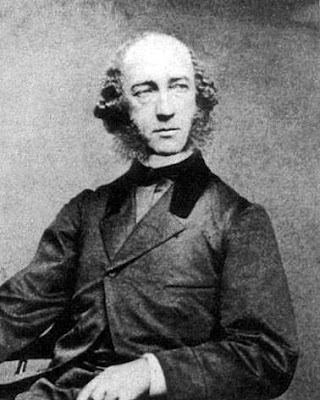

Martin Johnson Heade enjoyed limited success in his lifetime. He was an eccentric outlier of the second generation of the Hudson River School. Perhaps that came from his early apprenticeship to another eccentric outlier, the Quaker artist Edward Hicks. He certainly had ambition. He kept a studio in the Tenth Street Studio building where Frederick Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt kept their studios. After he died, Heade was largely forgotten and his work scattered. Before the 1920s, you could buy Heade's paintings in antique furniture shops in New York and London. His work enjoyed a revival of interest in the second half of the 20th century. It's the peculiar strangeness of his work, that quality of stillness before the storm pervades much of his work beyond his storm paintings. The hummingbirds, flowers, beaches, and marsh landscapes that make up most of his work have a strange obsessive and alien quality about them that is unmistakable but hard to describe.

Heade feared that he would live to see the end of the hummingbirds, and those remarkable small birds (among the smallest and the fastest in the world; an Anna hummingbird clocked in at 385 miles per hour in a mating dive, the fastest of all vertebrate animals). And now in our sad age, we fear seeing the end of all birds. Over the last 50 years, the bird population of North America declined by about 30%. Many hummingbird species verge on extinction due to loss of habitat and climate change.

The quote in the title is from the photographer and natural history writer Jon Dunn from his book The Glitter in the Green: In Search of Hummingbirds.

Few things give me more pleasure and hint at paradise than the glimpse of hummingbirds. I can't imagine a world without them, but everyone from Martin Johnson Heade to Jon Dunn warns us of their imminent end. Their end would be a harbinger of our end since in so many ways we are far more delicate creatures than the hummingbirds.

Stripe Breasted Star Throat

Tufted Coquette

White Vented Violet Ear

Blue Morpho Butterfly

Heade intended to publish this with his hummingbirds.

Orchid, Hummingbird, and Waterfall

Two Hummingbirds

Hummingbird and Two Orchids

The Brazilian Forest

Photo of the artist

No comments:

Post a Comment