Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys of Heaven to St. Peter, a fresco in the Sistine Chapel

You can see The Domes of Rome 1 here.

You can see The Domes of Rome 2 here.

At the end of the 15th century, Rome was a wilderness of ruins. The city long ago contracted to less than a quarter of its original size. The remains of the ancient city of more than a million people formed a tangled maze of broken masonry and stone covered in wild vegetation. Crime and banditry thrived in the ruins and farmers herded cattle and sheep where senators once walked. Rome was a poor city despite its sanctity and the presence of the Pope. Most of the enormous ancient churches that generations of pilgrims traveled far and at great risk to see were crumbling and badly in need of repair. The south wall of St. Peter's faced imminent collapse. Last minute buttressing and temporary repairs prevented the worst from happening but didn't solve the problem.

The great city states of northern Italy, especially newly rich Florence, over-awed the crumbling splendors of a mostly ruined and uninhabited city with their new and magnificent cathedrals and palazzi publici. Those cities all boasted links to ancient Rome. The revival of Classical culture in the Renaissance gradually inspired the ambition to rebuild Rome as a world capital once again, but this time of an empire of souls in the Church. That ambition would expand as a succession of popes, artists, and architects engaged in two century long effort to build Rome anew.

In that ambitious rebuilding of Rome, the dome returned to the city that made such structures great and inspiring. The city of Florence topped their cathedral with a dome that surpassed in height and width the ancient Roman Pantheon. By the end of the 15th century, there was a determination to return such ambitious construction to the very city that inspired all of it.

Toward the end of the 15th century, Italian architects from Alberti to Leonardo da Vinci dreamed of domed centralized churches, taking their inspiration from the writings of Vitruvius whose books on architecture are the only writings of their kind to survive from Antiquity. Because of this association with Vitruvius, historians for a long time associated this shared vision of the church as a centralized domed building occupying the center of a broad open plaza as a kind of pagan revival. As Peter Murray points out in his book on Italian Renaissance architecture, this notion is mistaken. Most Roman temples were four square buildings occupying one end of a columned forum. There were some round temples, usually built for goddesses, especially Vesta. There are ancient Christian precedents for round churches, such Santo Stefano and especially Santa Costanza in Rome. Both of those buildings were martyria, built not for congregational worship, but for rituals of circumambulation around the tombs of martyr saints or other holy places.

These architectural visions of domed churches in central plazas for a long time appeared only in paintings such as the famous examples by Perugino and Raphael above. At the beginning of the 16th century, the architect Bramante finally built one, though small in size, in Rome. Bramante arrived in Rome from Milan in 1499, part of the exodus from Milan following the fall of its ruler Lodovico Sforza to the invading French. In 1502, he completed the Tempietto in a cloister of San Pietro in Montorio in the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome on a site revered by some as the site of St. Peter's crucifixion (the current consensus places the location of that event on the spina of the Circus of Nero on the south side of St, Peter's Basilica). This beautiful small building announced the advent of High Renaissance architecture and created a lasting influence on later generations of architects down to the present day.

The Tempietto was the gift of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain to the monks of San Pietro in Montorio and to Rome.

The Tempietto in San Pietro in Montorio in Rome.

The architects of the Renaissance were indeed out to revive Classical culture and Classical art and design, but not necessarily to imitate it literally. They wanted to adapt it to the purposes of a new religion and a new era. Brunelleschi revived classical forms and proportions, adapting them to medieval design and construction methods. Alberti advocated a closer study of design and proportion emphasizing the monumental scale and volumetric aspect of ancient Roman architecture. Bramante in the Tempietto looking at the ruins of Roman monuments through through eyes instructed by Brunelleschi and Alberti revived that central idea in Classical design of completion. The building is whole and complete in the same way that our bodies are whole and complete. Nothing more may be added without distorting the design, and nothing large or small may be removed without mutilating it. Like us, it is whole and complete with all of its parts relating to each other in function and proportion resolving all into something as splendid and healthy as an athlete's body.

Temple of the Sibyl, Tivoli, 1st century BCE, possibly a temple to Vesta.

Bramante modeled the Tempietto after Roman round temples such as the Temple of the Sybil in nearby Tivoli. Like those temples, it is a masonry cylinder surrounded by a circular peristyle.

Santa Constanza, Rome, 4th century.

Bramante also found inspiration in early Christian martyrium churches, especially Santa Costanza in Rome, built for the rite of circumambulation with the addition of clerestory windows to a second story above the columned ambulatories.

Bramante combined and beautifully harmonized these two influences in his design, a first story surrounded by a circular peristyle, and a second story recalling the second story clerestory of an ancient martyrium church.

Even in the details, Bramante takes ancient Classical precedents and adapts them to the needs of the Christian religion.

The entablature of the Temple of Vespasian in Rome with carved reliefs of sacrificial implements. Completed in 87 CE.

The entablature of the peristyle of the Tempietto showing implements of the Christian Mass, inspired by the frieze on Vespasian's temple among other sources.

The Tempietto today is not quite what Bramante intended. The dome was modified in the 18th century. The drawing above from Bramante's workshop shows us the more hemispherical dome he intended and actually built.

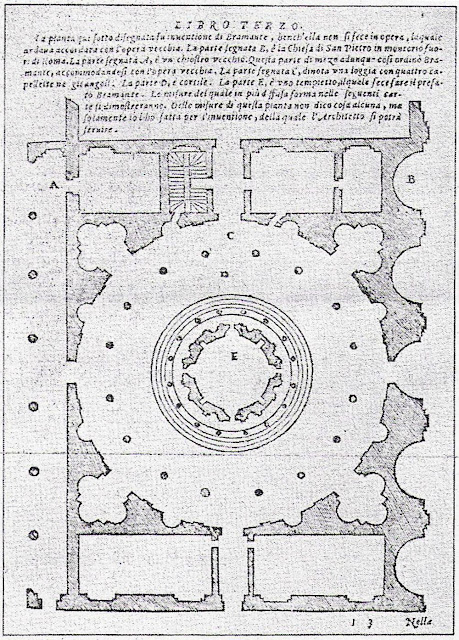

This print from Serlio's Architecture shows something else Bramante intended but was never built. The Tempietto sits a little awkwardly in a narrow cloister yard. Bramante wanted to put the Tempietto in the center of a spacious circular and columned courtyard. Our experience of it would have been so different had that courtyard been built.

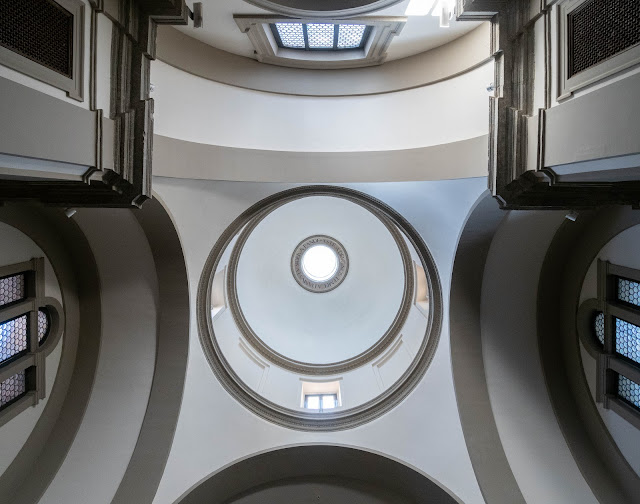

Some pictures of the very small interior of the Tempietto.

The Tempietto was the first domed structure built in Rome since the completion of Santa Costanza about a thousand years earlier. Its appearance announces the beginning of the long project to rebuild Rome as a world capital once again.

The Chigi Chapel

Another important domed building in Rome adjoins the Augustinian monastery church of Santa Maria del Popolo right next to the Porta del Popolo facing the Piazza del Popolo, for many centuries the main entrance to the city for religious pilgrims traveling south down the Via Flaminia. One such pilgrim was the young Martin Luther in 1510, then a young Augustinian monk who stayed as a guest in the monastery still attached to Santa Maria del Popolo.

In 1507, Pope Julius II granted Agostino Chigi, the chief banker and financier of the Vatican Curia, rights to build a burial chapel for himself and his family attached to Santa Maria del Popolo. The Chigis were a very wealthy and powerful banking family from Siena in Tuscany. In about 1512, Agostino Chigi hired the artist Raphael to design and build this chapel. Construction began on it in 1520 shortly before Raphael's death the same year. Construction continued in fits and starts under many subsequent artists until it was finally finished in 1670 under the direction of the great Baroque sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini.

The exterior of the dome of the chapel from the north side of the church across the Aurelian Wall.

The entrance to the chapel from the interior of the church.

The sumptuous interior of the chapel with paintings by Sebastiano del Piombo over the altar and on the walls and vaults by Francesco Salviati. The sculptures in the niches are Jonah by Lorenzetto who was Raphael's reliable in house sculptor, and Habakuk and the Angel by Bernini from about a century later.

The pyramidal tomb monuments to Agostino and Sigismondo Chigi were designed by Raphael and completed with modifications by Bernini.

The pyramidal tomb monument to Agostino Chigi designed by Raphael with modifications by Bernini. Pyramidal tomb monuments were unusual, but not unheard of in Roman churches. It is likely modeled on the ancient

Pyramid of Cestius near the Porta San Sebastiano in Rome.

Bernini's superbly dramatic sculpture of Habakuk and the Angel completed in 1661.

The sculpture is one of a pair by Bernini based on a relatively obscure story in the Book of Daniel where the Prophet Habakuk made lunch for reapers in a field in Judea. An angel appears to him and orders him to take that lunch to the Prophet Daniel locked up in the lions' den in Babylon. When Habakuk protests that he's never seen Babylon, the angel picks him up by the hair and carries him to Babylon and sets him before the starving Daniel in the lions' den with a fresh lunch. The angel then returns Habakuk to where he came from.

Bernini's sculpture of Daniel waiting in the Lions' Den.

The dome mosaics are based on designs by Raphael and executed by Luigi di Pace in 1516. They show the Seven Planets under the divine influence of God the Father who appears in the oculus at the top of the dome.

Agostino Chigi took a keen interest in astrology. One of the painted ceilings in the pleasure palace he built for himself across the Tiber from Rome (now known as the Farnesina) may show his star chart as interpreted by the Sienese artist Baldassare Peruzzi. The mosaic cycle in the dome reflects those astrological interests and beliefs.

The oculus mosaic of God the Father.

Raphael's splendid drawing for God the Father, probably based on a model drawn from life in red chalk.

The mosaic of the planet Mars with a guiding angel in he dome.

Raphael's magnificent drawing for Mars and his Guiding Angel, probably drawn from life from two models.

The pietra dura skeleton designed by Bernini in the floor of the chapel directly under God the Father in the Dome. The inscription in Latin says "Through Death to Heaven." The skeleton holds the the stemma, the coat of arms, of the Chigi family.

Sant' Eligio degli Orefici

Raphael designed and built this church about the same time he was painting the great frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura and is a sharp contrast to the later sumptuous Chigi Chapel.

Like the Chigi Chapel, this too was mostly left to others to build and complete such as Baldassare Peruzzi who probably designed the dome. The early 17th century facade was built by Flaminio Ponzio.

The splendid but very spare interior is mostly Raphael's own design and contrasts sharply with the elaborate splendor of the Chigi Chapel, even though the plans and sizes of the two domed chapels are very similar.

The church was built for the goldsmith's guild in Rome, St. Eligius of the Goldsmiths.

San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

As the name says, this church was built for the Florentine congregation in Rome. The present church was designed and built by Giacomo della Porta based on an earlier design by Jacopo Sansovino with some later modifications by Alessandro Galilei, a descendent of the great scientist Galileo.

Pope Leo X, a Florentine and a Medici (Giovanni de Medici) ordered the church built to replace an older church dedicated to Saint Pantaleon.

The facade by Alessandro Galilei completed in 1734.

Interior of the church

The dome built by Carlo Maderno, a circular interior with an octagonal exterior recalling the great octagonal dome of Florence Cathedral.

In 1559, Duke Cosimo I de Medici commissioned Michelangelo to submit a design before construction began in earnest upon the church.

Michelangelo experimented with several centralized designs for a great domed church in a series of magnificent architectural drawings.

An engraving of a wooden model for Michelangelo's final design for San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. It was not used. The congregation continued with the original design by Sansovino.

St. Peter's

I've discussed the redesign and rebuilding of St. Peter's before on this blog at length

here and

here.

The greatest dome in Rome, and among the greatest in history, curiously does not quite dominate the city in the way we would anticipate. It stands off to the side of the city at a distance. If we stand on a hilltop just about anywhere in Rome, we can see it on the horizon looking like a distant mountain, more like Mt. Fuji on a clear day from Tokyo instead of dominating the whole city like the US Capitol dome over the center of Washington DC.

The Vatican hill was always just outside ancient Rome on the west side across the Tiber. Until the mid 20th century, the territory on the other side of the Vatican was open countryside to the sea coast.

Adding to the unusual aspect of St. Peter's in relation to its city is the fact that it is not built on a hill top, but into a hillside, for centuries a continuing challenge for construction inspiring much structural innovation.

The dome of St. Peter's crowns the largest single building construction project in Rome's long history. Construction on everything we see now took around a century and a half to complete. St. Peter's remains the largest church ever built, even in our age of prodigious construction enabled by new and newer technologies. Its dome is still the tallest in the world, at 447 feet (136 meters). All the other great domes of the world would fit comfortably within its vast interior like nested Russian dolls with room to spare.

.jpeg)

Rising over the historically most important Christian altar in the Western world, the great dome designed by Michelangelo rests on a crossing designed and built by Bramante and contains within its form the entire history of the Western Church to the 16th century. The dome is an architectural form identified with ancient pre-Christian Rome. It recalls the round paintings on the ceilings of cubicula in the catacombs of the third century. The dome calls to mind the round martyrium churches built over the tombs of martyr saints after Christianity was legalized by the Emperor Constantine. The huge dome rests on four great arches, a creation of the Byzantine Empire and Eastern Christianity. The emphatic ribbed verticality of the dome inside and out reminds us of Gothic art with its great cathedrals.

So much meaning and association concentrated into a clear concentrated form on a great scale that only someone with the intellectual strength and confidence of Michelangelo could bring off.

The lantern of St. Peter's crowded with tourists.

A pope's eye view of the Baldachino over the altar of St. Peter's and the dome beyond.

Etienne Duperac's engravings of Michelangelo's proposed designs for St. Peter's.

A photo of St. Peter's from the west taken in the 1890s, a view now obscured by a lot of early 20th century construction after the Vatican became an independent state within Italy. As we can see, until recently the countryside came right into what are now the Vatican gardens.

I show this photo because this is a view of Michelangelo's best and most ambitious work on the exterior of the church that is no longer possible. Vatican administration buildings from the 1930s now block most of this view. The general public, tourists and all, are not admitted to see this view except for bits and pieces of it from windows and balconies in the Vatican Museums.

Also, we can see much more clearly in this photo than we can now how St. Peter's is built into a lower slope of the Vatican hill.

.jpeg)

__rome__italy__ca_337-3511361846597261.jpg)

_-_2021-08-25_-_2.jpeg)

_HDR.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)