Yesterday was the birthday of Georges Seurat, an artist little appreciated in his short lifetime. He died in 1891 at the age of 31 probably from meningitis. He's famous now, but mostly for a single painting, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte now in the Art Institute of Chicago. And the aspect of the painting that now intrigues most viewers is that it's painted entirely in points of single divided colors that when viewed from a distance come together to make browns, purples, greens, etc. -- pointillism. Indeed, Seurat prophesied the pixels on the monitor you are using now to see this post. The late Stephen Sondheim made Seurat's painting immortal in his musical Sunday In The Park With George.

I've always been fond of the painting he made just before La Grande Jatte. Seurat was only 24 when he painted this his first truly ambitious painting to introduce himself to the public, Bathers at Asnieres in 1884.

The painting now in the National Gallery in London shows a group of bathers, all men, taking a dip in the Seine or just lounging on the bank. This is an actual spot about 4 miles from the historic city center of Paris. In the background are the factories and gasworks of Clichy,

the same ones that Vincent Van Gogh would paint from a different angle in 1887. This is part of the north bank of the Seine just across from the Isle de la Grande Jatte. We can see part of that island sloping down into the river on the right.

It is a bright hot summer afternoon full of humidity, a perfect day for a swim especially at a time before air conditioning or even electric fans. The heat and humidity impose a stillness upon the scene. There is very little movement. The men involved sit still in the heat and do not talk to each other. Only the young man on the lower right in the water seems to be yelling or whistling at someone outside the picture frame.

Other than these men, we see a small boat with some bourgeois passengers with a top hat and a parasol being rowed in a boat conspicuously displaying a French flag gone still in the heat of the day. On the far right is a racing rower about to disappear off the framing edge. Three sailboats somehow find enough breeze on so still a day to fill their sails on the river.

The factories of Clichy in the background.

Maps and guidebooks of the time identified this spot on the Seine as a place of leisurely bathing, but it was not exactly luxurious. It was likely very noisy and smokey from not only the factories but the busy railroads in the area. We can see a railroad bridge in the background with the factories. One of the smokestacks in the painting belches smoke, but does little to break the stillness or cloud the brilliant afternoon light pervading this painting. Indeed, these factories look less like 19th century industrialism and more like the classical temples in the background of a Poussin painting and that's not accidental.

Nicholas Poussin, The Finding of Moses, 1638 in the Louvre

Georges Seurat was a dutiful and loyal alumnus of the Ecole des Beaux Arts. He willingly immersed himself in the grand monumental tradition of French public classicism. He was no radical eager to blow up the establishment. He took seriously the lessons of the conservative professor Charles Blanc who encouraged a return to regular drawing from the cast collection and had large copies made of frescoes by Renaissance Italian masters, in particular Piero della Francesca. Blanc in his book La Grammaire des arts du dessin from 1867 argued that this painting of the Finding of Moses by Poussin was the epitome of monumental classical painting. It takes a moment from time and elevates it to stand for all time through idealization of natural form. Seurat read this book and took its ideas very seriously and applied them to The Bathers at Asnieres.

We look at The Bathers comparing it to the work by Poussin and at first The Monumental would seem to be the very last thing on his mind. Poussin painted a pivotal moment in the Biblical narrative of the Exodus of Israel from Egypt. Seurat paints a moment that is anything but pivotal, a bunch of men on their day off taking a swim. Just look at the figures Seurat shows us in this painting.

The center bather

This figure dominates the finished painting and the many small oil studies Seurat made for it. He's hardly Apollo. He wears a wet mop of auburn hair on a pale body that is young, but not exactly that of a champion athlete. He has a bent nose and a very pronounced over-bite. He's no beauty. He sits in a pose that we've all seen by a hundred swimming pools, that young man's slouch, shoulders bent over stomach like an anchovy. His clothes lie casually discarded in the grass beside him. He's likely a tired employee of one of the factories in the background on his day off. And so are all the other men on the bank. The bowler hat worn by the man lying on the grass on the left with his dog reveals the class of the bathers on this bank.

A drawing probably from life for the center bather in Bathers at Asnieres

And yet, as graceless as this central young man is, Seurat tries to give him and his companions something of the grandeur of the sculptures of the Parthenon without falsifying them or their situation. He generalizes their facial features and shows them mostly in profile. Not only does he show them not talking to each other, but they make no effort to engage us. Seurat also keeps the light and dark contrasts relatively minimal for a bright hot day. He keeps his figures as motionless as statues.

He also monumentalizes them through composition. Seurat pays particular attention to the pictorial architecture of Poussin in both 2 and 3 dimensions. Like Poussin, Seurat uses a series of repetitive and echoing forms to take us in stages back into the distance. The contours of the bank on the left repeat themselves at regular intervals as they go back toward the railroad bridge and factories. Those contours also repeat the contours of the young man lying on the bank on the left. He has a small distant twin wearing red. The young man seated in the straw hat also has his twin wearing a white cotton suit with a bowler hat behind him. That young man in the straw hat establishes the horizon line that appears as his (and our) eye level, made visible by the railroad bridge proceeding from left to right. The slopes of the north bank of the Seine find their inverted echo in the distant bank of the island of La Grande Jatte on the left.

Like Poussin, Seurat uses ratios in his composition, in this case a classical ratio of 1 to 3. He divides his canvas vertically by thirds. The sky fills the top third. The seated men dominate the middle third and the reclining man with his dog dominates the lower third. Also as in a Poussin, figures, boats, and trees appear in overlapping groups of three. This kind of compositional architecture may be monumental French classical form as interpreted by

Puvis de Chavannes, a painter loved by everyone from conservatives such as Flandrin and Corot to radicals such as Gauguin and Picasso. The isolated figures evenly distributed along with the chalky color come straight out of Puvis' work. My professors loved Puvis and always recommended him to us.

Why such a monumental treatment of low wage workers on their day off?

Seurat had left wing political sympathies. Certainly by contemporary American standards (that are now trending to the right of Mussolini and Franco) Seurat would definitely be considered "socialist." He probably would not mind the moniker. Like many socialists and others from the left, Seurat believed that it was labor, not capital, that created value. He gave these tired working men a sense of monumental grandeur because he believed that they and their labor were the foundation upon which modern society rested. In this Seurat differed from many of the Impressionists whose work he very much admired. With the exception of Pissarro, most of the Impressionists were politically center right in their politics (Degas was far right and explicitly racist and antisemitic in his views).

Seurat may have intended this small detail of a bourgeois couple in a boat with the French flag to be a kind of foil for the men and boys bathing in the river. The representatives of capital may claim the flag and all it stands for, but the people who labor in the factories in the background make it.

The splendid man in the bowler hat with his even more splendid dog.

A study for the man in the bowler hat.

The young man in the water calling or whistling

A beautiful conte crayon drawing probably from life.

Seurat made this painting before he debuted his fully developed pointillist technique in Sunday Afternoon of the Island of La Grande Jatte. He began that large painting as soon as he finished this large painting. Already as he was working Bathers at Asnieres Seurat was reading books on new theories of color and optics by Michel Eugene Chevreul and Ogden Rood among others. This loyal son of the establishment Ecole sought out the then radical works and views of the Impressionist painters. He admired the Impressionist attention to modern subject matter and the "look" of modern life. He also admired their attention to color and its workings, so different from his professors such as Charles Blanc who certainly took color seriously but put it underneath drawing and chiaroscuro in the hierarchy of what mattered most.

Seurat did not care much for the spontaneity of Impressionism, working immediately to capture a fleeting light effect. He thought it too ephemeral. Seurat probably would not be sympathetic to the modern and post modern convention of seeing art as a process and not as a final work.

For a pioneer of modernity, Seurat was very traditional in his conceptions and approach to work. He thought very much in terms of a finished painting to be realized through a process of experimentation and refinement getting to that fully distilled perfect articulation of an idea. He made studies, sketches, and drawings from life, something that no Impressionist would do, but Raphael and his followers did for generations.

The color is probably the most modern aspect of this painting. It is based on the chromatic palette of the Impressionists and discards the traditional tonal palette of classicism. The chromatic palette developed by the Impressionists organizes brilliant colors according to the order of the spectrum and uses them as such on the canvas. Seurat regularizes the once spontaneous Impressionist brushstroke that sought to break down the hierarchy of emphasis in painting giving every aspect of the scene the same attention. Before he began to break up mixed colors into dots of pure color, he created a variety of regular organized choppy strokes of color on color.

On the figure of the seated young man in the straw hat on the left are what were probably black pants. Here Seurat painted those black pants using a chromatic palette first with cool blues and violets and then highlighting them with warm oranges. Brush strokes are scumbled over other brush strokes creating a matte effect.

A grassy bank next to the water begins as a field of green and blue. Thin strokes of dark green, white, and orange add the sparkle of light to the grass. Strokes of violet and lighter blue over the blue of the water do the same for the river.

This careful use of the Impressionist palette recreates with amazing refinement the look of sunlight on a bright hot afternoon without resorting to blacks or umbers for the shadows.

The very classical practice of making a series of oil sketches of the whole composition, what in the Ecole was called a précis.

The practice may be very classical, but the choice of subject matter and the use of color is very modern.

Seurat gives us an unusual glimpse into the evolution of his thinking about this painting.

The painting today in the National Gallery in London

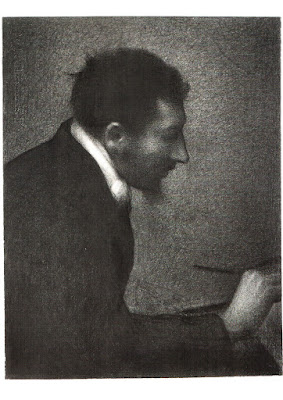

A self portrait by Georges Seurat

No comments:

Post a Comment