Blade Runner (1982)

When Blade Runner first came out in 1982, it promptly flopped commercially. The kids at the suburban cineplex (who still are the bread and butter of Hollywood) were bored with it. No light saber duels, no cool monsters, no whizzing spaceships all over the screen, just a lot of atmospheric anxious dread. It was only years later that the public began taking a second look at the movie, mostly the older public. The critics soon followed and began revising their previously tepid reviews of the movie. For a long time the movie had a kind of cult following, and now is generally reckoned among the great classics of science fiction.

I was around in 1982 and vaguely remember when it came out, but I didn't see it until maybe the 1990s. I've seen it many times since. I think it's one of the most lushly beautiful science fiction movies ever made. I love the atmosphere, the constantly shifting light, the use of color, and I especially love that glamorously dying dark Los Angeles of an imagined 2019. Blade Runner made me think a lot not of Los Angeles, but New York of the early 1990s where I found myself when I first saw it. It looked so much like an even more glamorous version of already glamorously decadent New York just before the big waves of gentrification hit Manhattan and later Brooklyn. That movie still influences the way I see New York and the way I paint it. I think of a phrase from Hannah Arendt, "... the cruel splendor of a new age."

The movie came out right at the dawn of four decades of reactionary politics determined to roll back the Civil Rights Movement and the social and cultural transformations that came out of the decade of the Vietnam War. That long reaction also tried to destroy the legacy of the New Deal. A culture of expectation became a culture of nostalgia, and stayed there for forty years (though those processes of social and cultural transformation continued sometimes underground, and sometimes joined with technological transformation). Blade Runner is neither hopeful nor nostalgic. It anticipated the fulfillment of the grim social Darwinist ideology of Supply Side Economics. It envisioned a world thoroughly despoiled by profit driven exploitation so badly that people were encouraged to emigrate to the "off world" colonies. Immense powerful corporations like Tyrell eclipsed what little was left of the public realm, of government and the rule of law. In this hyper-monopolistic commercial world slavery makes a comeback in the form of manufactured people with superior strength and abilities with a fail-safe lifespan of only 4 years. Four of those slaves rebel and return to earth hoping to force their creator Tyrell and his corporation into lengthening their lifespans.

Blade Runner is a dark vision of the world coming into being in 1982, a vision of what might happen, a dystopia. I sometimes think of dystopias as utopias exposed to light and air. The dominant ideology of the beginning of the 1980s was utopian though it was not a generous utopia like Thomas More's original story of that name. It was a Valhalla of the winners with its hard cruel visionaries like Ayn Rand. That utopia of the winners of capitalism would come at the price of creating a hell, a dystopia for everyone else. Blade Runner was a vision of that hell.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

The sequel to Blade Runner that came out in 2017 suffered a fate similar to that of the original movie. Critics were divided over it. The Blade Runner cultists faulted it for not being perfectly faithful to the original. And the public was largely indifferent to it. It was a box office fizzle.

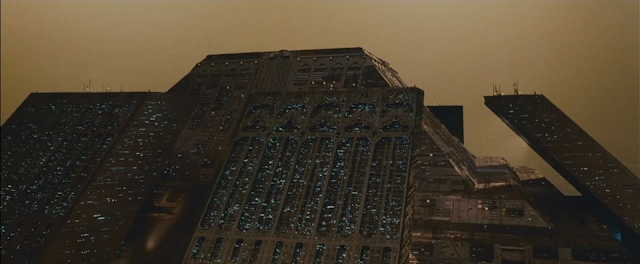

I liked it better than the critics did. Its vision of Los Angeles in 2049 doesn't have the glamour or sex appeal of the 1982 movie, but I don't think that's a problem. The 2017 sequel is much more thoroughly a dystopia, and an even grimmer and more frightening one at that. Los Angeles in 2049 is literally darker than the city of the 1982 movie. Most of the city is crowded housing in the dark from short supplies of electrical power with lights confined to major thoroughfares. As far as I'm concerned, that's as it should be. Dystopias are visions of hell. Hell is supposed to terrify, not allure. The sequel is true to the visionary and atmospheric qualities of the 1982 movie in spades. I think the sequel is every bit as beautiful, if darker and more menacing, as the first Blade Runner movie. It uses the same atmosphere and shifting light to much more foreboding effect. The use of color is even more beautiful here than in the 1982 movie.

Fritz Lang, Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang's Metropolis is the first great dystopian cityscape in the movies. It is the great grandfather of the Blade Runner movies and all movies like them. Metropolis was a huge hit across Europe and eventually globally. Even so, the expense of making the movie was so great that it bankrupted Ufa, its producer and distributor.

New York inspired the creation of Metropolis. Lang and his then wife Thea von Harbou came up with the idea for the movie and the story while visiting New York City in 1924 and seeing its soaring skyscrapers and sprawling city streets.

Metropolis remains controversial almost a century later because of its politics. It was politics that drove Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou apart and caused Lang to ultimately disown this movie in later life.

Lang and some of the other actors in the movie such as Gustav Fröhlich and Brigitte Helm opposed the Nazis emerging as major political players in 1927. All of them would eventually refuse to work for Hitler and leave Germany. Others such as Heinrich George remained in Germany and worked willingly for the Nazi regime. Thea von Harbou enthusiastically supported the Nazis from the beginning. Lang divorced her because of her political loyalties. The Nazis loved the movie (to Lang's chagrin). They loved the idea of a messianic leader bringing classes together for the sake of a larger national identity. That was the theme of a lot of von Harbou's writing before and after Metropolis.

Metropolis had its right wing critics who saw the movie as latently communist for its overt sympathies with the workers. Left wing critics hated the movie for showing the workers as easily manipulated crazed witch-hunting savages goaded into a self-destructive rebellion by an agent of their employer.

Most other critics such as HG Wells found the movie's plot ridiculously naive and simplistic.

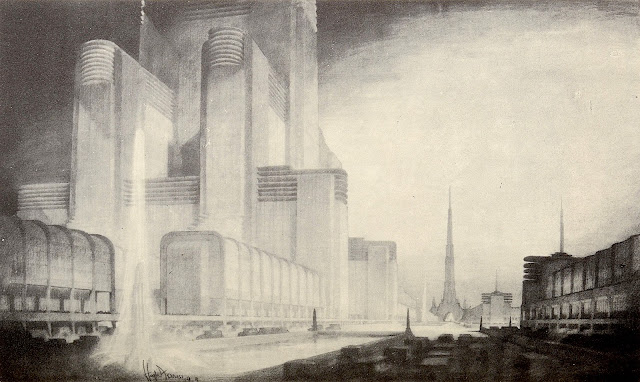

What people then and now loved about the movie was the Metropolis itself, the first great dystopian spectacle in the movies that would have such a long influence on later films. Lang imagined a vast out of scale city as a giant money-making machine benefitting a small favored elite at the expense of a vast exploited proletariat that lived underground. It's a busy city full of traffic, cars, busses, trains, and even planes buzzing constantly through the vast canyons of the city (certainly inspired by the urban canyons Lang saw in New York in 1924). The Metropolis is a thrilling spectacle, especially at night lit up by the still new technology of electric lighting. It's the fulfillment of the city as chaotic spectacle foretold by the Italian Futurists a couple of decades earlier. It's Futurist architecture that so far existed only on paper brought to life.

Hugh Ferriss, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, 1929

What began for architectural illustrator Hugh Ferriss as a hypothetical project looking at the promises and perils of the New York City 1916 building code mandating stepped back buildings to allow light and air to the street level eventually evolved into a much bigger project imagining a future New York City. Ferris created a series of fantastic imaginary prospects of the Art Deco architecture of his day that was already vast in scale taken to even more extreme scale. In doing so, the tone and mood of the whole project changed from a sunny chamber-of-commerce optimism to a kind of unaccountable gloom and dread. For these drawings Ferriss chose a very unusual medium for architectural drawings, conte crayon. Conte crayon is for large and rich plays of light and dark. A fine conte drawing conveys atmosphere. It does not do well in the fine detailing usually required for architectural rendering. Ferriss used conte crayon for precisely that purpose, to create atmosphere and mood for his imaginary cityscapes.

The exact time of day is never quite clear in his drawings, nor is it even clear that we are looking at daylight. There is a perpetual twilight of descending gloom in Ferriss' work.

Ferriss' melancholy and anxious Metropolis of Tomorrow calls to my mind the great photographers of New York of the 1930s and 40s, such as Berenice Abbott, Andreas Feininger, Samuel Gottscho, and Irving Browning. Their dramatic photos of the city convey a similar inexplicable dread in their strong contrasts of light and dark, that there is something exhilarating and vaguely monstrous about vast city they photographed. So too in these visions by Ferriss.

Antonio Sant' Elia, Futurist City, 1912 - 1914

Antonio Sant 'Elia built very little in his very short career as an architect. He died in 1916 at age 28 on a battlefield in the First World War. We remember him best today for a series of drawings he made from about 1912 to 1914 of imaginary buildings of the future. Sant 'Elia was closely involved with the Futurist movement in Italy that formed around the poet Filippo Marinetti. Like other Futurists, Sant' Elia wanted to make a clean break with the past. The Futurists felt the heavy weight of a long history that hangs over Italy, a very ancient country. Marinetti wrote of flooding the museums to break free from what they felt was the oppression of the past. Churches, palaces, and civic buildings are conspicuously absent in Sant' Elia's imaginary cities. Most of the buildings in his cities are involved with transportation from railroad stations to airports that didn't quite yet exist, but he imagined them. Sometimes Sant' Elia designed utilities such as power plants and water works.

Modern design that radically imagined a whole new technological future began in two countries heavily weighted by the heritage of an ancient past, Italy and Russia. Both countries were the first to take what was implied in Cubist painting and sculpture and apply them to everything from graphic design to architecture. Sant Elia's buildings in particular still look remarkably forward-looking for the eve of World War I. Sant' Elia's first big influence was on science fiction illustration in the first half of the 20th century. Sant' Elia intended his designs to be hopeful, greeting the dawn of a new era freed from the prejudices of the past. A lot of feeling comes through in his work, especially wonder and excitement over a future he would not live to see. That perhaps is what the science fiction illustrators responded to.

Like the creations of the first generations of Russian modernists, these drawings for all their rationalist empirical pretensions are deeply emotional, romantic imaginings of a much hoped for future.

Piranesi, Carceri d'Invenzione, 2nd edition, 1761 -1768

The Prisons of Giovanni Battista Piranesi are perhaps the first visions of dystopia, that mixture of dread and exhilaration at an imaginary future at the heart of so much modern science fiction. While Piranesi called these entirely imaginary prospects "prisons," they don't look much like prisons except for occasional chained prisoner here and there. It's hard to say what they look like, but they have that strange mix of grandeur and disorientation that's in the best imaginary dystopias in literature and movies.

These prints are from a category of art at the time called "caprices," fantasies created by the artist. A lot of artists made these caprices, even Canaletto. Goya turned the artist's caprice into biting satire and frightening irrational visions of chaos and death. Piranesi devoted much of his life to archaeology in the service of architecture and design. He opposed Johann Joachim Winckelmann's sunny romantic imaginings of ancient Greece with the gritty realism of Rome, an ancient world that remained firmly in the past as Piranesi saw it. Piranesi saw the vast brooding monuments of ancient Rome as challenges for the emerging modern world.

Piranesi with Goya was among the first to imagine the perils of emerging modernity. Among those perils was a disintegrating sense of self confronted with a much larger and more impersonal environment. Complicated perspectives cross paths before us and seem to go nowhere. For all the carefully and rationally constructed perspectives in these prints, nothing is clear. There is no one path over others. There's nothing to clarify our sense of where we are and where we want to go. It's that sense of being lost, marooned in some vast and cold disorienting landscape that first appears in Piranesi's Carceri prints, and still speaks deeply to us.

Building Real Dystopias

It's hard to walk through just about any of the major cities of the earth and not think of everything from Blade Runner to Piranesi's Carceri. The vast impersonal forces of economics, local and global, shape modern cities and fulfill the darkest and most alienating fantasies conjured by artists for over two and a half centuries.

China

Rem Koolhaas' CCTV building in Beizhing.

No one builds vast frightening dystopian architecture quite like the Chinese.

The CCTV Tower and neighborhood in Beijing

The new city center of Beijing

Beijing Airport

Even more terrifyingly dystopian are Chinese housing blocks.

Dubai

Dubai, the biggest and grandest of all dystopian cities, the unofficial capital of the international plutocracy and the preferred haven from taxation and extradition for the world's most astonishingly wealthy. It's a huge city seemingly sprung up out of empty desert overnight. It's home to the world's tallest building, and to other construction projects so vast they can be seen from space.

Dubai is a city of amazing splendor and incredible luxury sustained by a vast army of semi-slave labor.

Ashgabat

If Vladimir Putin ever gets to build a new capital city and name it Putingrad, or Donald Trump succeeds in making himself President for Life of America and wants to build his own new capital of Trump City, both of those projects would almost certainly look like Ashgabat.

Ashgabat is the new capital of Turkmenistan, built like Dubai in the middle of empty desert. Turkmenistan's late dictator Saparmurat Niyazov built this mostly uninhabited new city as his own Xanadu, shaped by his self conception as a kind of political messiah, a nationalist demigod ruling over his isolated and impoverished country.

All of Ashgabat's monuments for all their size and splendor ultimately look like bowling trophies.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment