I visited the Winslow Homer show twice at the Met Museum and had a great time. It was the biggest Winslow Homer show I'd ever seen, and the biggest one anywhere in twenty five years.

The curators did a great job organizing the whole exhibition around this painting, Homer's most famous, The Gulf Stream painted twice in 1899 and then reworked in 1906 four years before his death. Winslow Homer himself considered this to be a pivotal painting in his career, a tying together and summing up of all the thematic and formal threads that move throughout his work. The curators titled the show Winslow Homer; Crosscurrents.

The painting shows an unimaginably terrible predicament. A lone sailor lies on a boat adrift without a mast or a rudder, presumably lost in a storm. Some sugar cane spills out of the hold on deck. Sharks surround the boat in a frenzy anticipating a meal. The boat tosses about on huge storm swells. In the background, a storm that has just passed or another one coming on complete with a waterspout menaces the lone sailor and a distant ship on the horizon. We have no idea how this is going to turn out, though it looks very bad for the young man.

And yet, this man for all his peril looks remarkably unperturbed and self-possessed.

Below are some detail photos I took from the original with a very low-price phone camera.

All of these photos are from Wikimedia Commons or museum websites except for those that I took myself.

This thrilling cliff-hanger of a painting intrigued a lot people who asked about it. Homer gruffly refused all questions about the painting insisting that its whole meaning was in the title, The Gulf Stream. The curators of the show took Homer at his word and throughout the exhibit ask us to think about the Gulf Stream as something more than an ocean current that affects North American and European weather.

The Gulf Stream played a large role in the history of the Americas. It facilitated transatlantic commerce including the slave trade. The young sailor is a descendant of African slaves forcibly removed and settled in and around the Americas. Even before colonialism and slavery people fished the Gulf Stream waters for centuries and still do. The Gulf Stream plays a central role in creating the uniquely violent weather of North America (hurricanes on the coast and tornadoes inland) and the more temperate climate of western Europe. For millions of years fish and other sea creatures used its currents to migrate (if you look carefully at this painting you can see flying fish). The Gulf Stream as a painting and as a subject contains so many of the themes that pre-occupied Homer throughout his life such as: human life dependent on a vast terrifying nature utterly indifferent to human welfare; the sea as a vehicle of human history placing so many different peoples in unexpected proximity and the conflicts that creates; and the terrible struggle to survive shared by both humans and animals.

I thought of Bruegel walking through this show. Like Winslow Homer, making a living from indifferent nature preoccupied the great 16th century artist and drove so much of his innovative composition. Where Homer and Bruegel part company was emotional investment in their subjects. Homer feels real sympathy for his soldiers on the front and their families back home facing high risks and real peril, for the sailors of New England and Cullercoats in England and their families risking their lives to make a living, and for the Black descendants of African slaves in the very different tropical environment of the Bahamas doing the same thing. Homer even feels a certain sympathy for animals in peril either form natural forces or from human predation. Homer feels far more sympathy for all his sailors, soldiers, farmers, and hunters than Bruegel ever did for his peasants. Bruegel views them from mid air, the "angel's eye view." Homer puts us right on the ground or in a boat with his people.

Winslow Homer photographed in his studio working on The Gulf Stream, about 1899.

Here are a couple of my photos of the exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The curators arranged the show so that it always referred back to The Gulf Stream hung in the center with windows in some gallery rooms to take us back to it.

The label copy and wall text of this exhibition used the word "transformational" a lot. Indeed, Winslow Homer lived through the most transformational period of American history so far, the years of the Civil War and Reconstruction. He had a front seat for both.

Homer began his artistic career as an illustrator working for the big picture magazines of the day, especially for Frank Leslie's Illustrated News. Unusual for the time, Homer worked freelance, sometimes for two or three magazines at the same time. He was an early version of what we would call a photo-journalist. He toured the front lines of the Civil War, mostly in Virginia. Most of his subject matter was of army camp life. Only rarely did he make scenes of the actual fighting. It was during these tours that Home began nourishing ambitions to become a serious painter, a fine artist. His famous Civil War paintings were his earliest successful efforts as a fine artist.

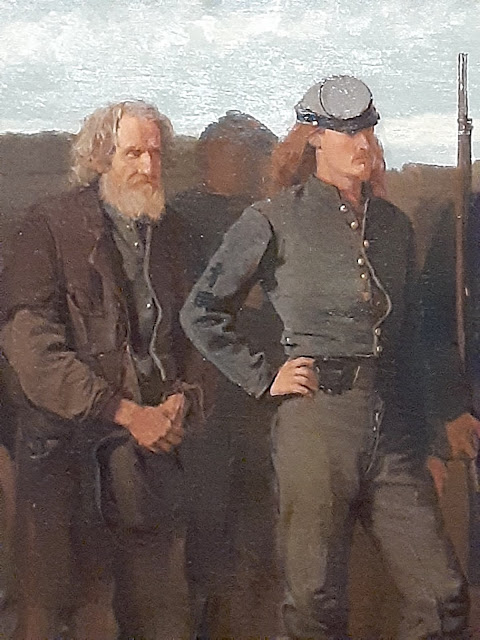

Like most of the other Civil War era fine artists of the day, Homer never showed the horrors of the battlefield and its aftermath. That was left to photographers such as Alexander Gardner and Matthew Brady. Unlike many of those artists who addressed the war metaphorically (artists from Daniel Chester French to George Inness), Homer painted the people caught up in the conflict directly. Above is Homer's most famous Civil War painting, Prisoners From the Front, painted in 1866 after the war was over. Homer made the painting out of General Francis Channing Barlow's capture of Confederate prisoners during the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse in 1864.

Below are some details I photographed from the original.

The very young Brigadier General Barlow, better dressed in Homer's painting than he usually was on the battlefield. General Meade scoffed that Barlow looked like a "a very independent mounted newsboy."

But Barlow was already a decorated war hero with a reputation for aggression in battle and coolness under fire, and rose very fast from the rank of private at the beginning of the war to brigadier general by 1864. He survived the war and went on to have a long political career.

Winslow Homer who never felt confident about doing portraiture did a fine job with General Barlow according to this photo.

Confederate soldiers taken prisoner in soiled and shabby uniforms looking both defiant and anxious about what will become of them.

The encounter between antagonists is something we will see again in Homer's work. Homer's painting summarizes the Civil War conflict between Southern audacity and Northern industry and resources. It is a confrontation of regional antagonisms and class conflicts.

Another painting from the Civil War series shows neither the front line nor a military camp. It shows the very real hardships on the home front. A couple of boys set up a primitive harrow made of tree branches to prepare the ground for planting. This was labor usually done by young men with rented tools. All the young men and their fathers are away fighting the war, and it's uncertain if they will return. And if they do return, they might come back maimed and unable to do farm labor.

The Civil War impoverished millions of people on both sides. Women and even more frequently children did the work of grown men. One boy sits on the harrow to give it more weight while another one gets ready to ride a very thin and underfed horse to pull it. The boy riding the horse looks as exhausted and miserable as his mount. This is a painting full of desperation and sorrow.

I think that there are few figures as sad as this boy, though we never see his face. The disproportion between him and his horse (he's almost too small) and the stoop in his back tell the whole story without ever having to reveal his face.

Photos I took from the original.

The younger boy on the harrow waiting to start.

Among the most emotionally tense and fraught of Homer's paintings is this scene from Reconstruction, A Visit From the Old Mistress, painted in 1876, the year of the squalid presidential election that would end Reconstruction and reunite North and South at the expense of African Americans.

The former mistress of the plantation visits her former slaves in their cabin. The formerly enslaved look at her with complex mixed emotions from defiance and resentment to something like pity. She wears black and is likely a widow. She may be telling them that she cannot pay them a salary and is selling the plantation. Or, she may be there to discuss wages with them.

Winslow Homer refuses to play to the presuppositions we might have about either side in this encounter. As impoverished as they are, the former enslaved women make no appeal for our pity or hers. Homer resists resorting to the usual stereotypes of African Americans that prevailed at the time. He certainly has sympathy for these wronged and brutalized people facing a new future full of hope and peril. But the old mistress is no monster either. She may not only be widowed by the war, but impoverished.

This is an emotionally fraught painting for us today, and certainly was for audiences in 1876. Homer stubbornly refuses to hint at any outcome in this meeting. Nor does he ever tip his hand where his sympathies ultimately lie in this situation.

Here are some photos I took of details from this striking painting.

The figure group of the formerly enslaved women makes a magnificent composition. The painting of their extensively patched and tattered clothes is also wonderful. My favorite figure sits on the left listening intently, not tipping her hand at all about what she thinks.

Another painting from Reconstruction shows two women working in a beautifully painted cotton field. Unlike most other similar paintings from that era painted by whites, the women have dignity and are sympathetic.

The Morning Bell, 1871.

Another painting from Reconstruction showing the transformations wrought by the war on the lives of those living in the North. A bell on top of a mill that probably made textiles summons employees to work in the morning. The beautifully illumined woman in the center is likely someone made poor by the war. Her dress and straw hat indicate a class formerly higher than the other women on the right who wear sunbonnets indicating field labor, though she goes to do the same work.

The United States industrialized in the course of the Civil War, a process that made some people very rich and impoverished others.

Homer was a wonderful painter and this is one of his best showpieces of composition and lighting painted at the same time Corot and the Barbizon School of landscape painters in France worked to introduce natural daylight into their landscapes painted from life.

Crossing the Pasture, 1872

Something else the Civil War created was an appetite for nostalgia. After so high a death toll with so many families suffering bereavement, the memory of the years before the war took on more and more of a golden tone for many people. Winslow Homer was no exception as he shows two farm boys, probably brothers (perhaps a memory of his own childhood with his older brother Charles), crossing a pasture that belongs to a bull in the background on the left. The younger boy clearly is anxious and clings to his older brother. Like many other painters, Homer painted a lot of nostalgic subject matter to meet public demand in those years.

Homer spent two years (1881 - 1883) in Cullercoats, a coastal village in the far north of England in Northumberland. The inhabitants made a precarious living fishing the stormy waters of north Atlantic risking their lives. During these years, Homer's palette grew more somber with grays and umbers, and his sense of form gained a new largeness, concentration, and seriousness of purpose that it didn't quite have before. His work gained a certain monumentality. I can't help but think that before he went to Cullercoats, the time spent in the British Museum and the National Gallery was productive for Homer, learning a certain grandeur and clarity of form from the art of the past. He then applied it to paintings of the lives of fisherfolk and their families on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Gale, 1883 and reworked sometime before 1893. He made this painting in Tynemouth in England bringing it with him back to the USA where it hung in his studio in Prout's Neck, Maine for many years. It shows an anxious wife with her child braving the gale to see if she can see any sign of her husband.

Homer makes a much larger and simpler composition than in the past dominated by the large figure of the young woman braving the storm. For the first time as well in his work, the sea plays a major dramatic role dominating the bulk of the canvas. It's churning waves and distances as the waves crash against the rocks on the left make it frightening.

The Fog Warning, 1885

A painting that uses very effectively the grandeur of form Homer learned in England. His compositions are much more concentrated and to the point with, in this case, a single figure.

A lone fisherman with a couple of large halibut in the stern of the boat rows back to his ship. He looks over his shoulder to see an approaching fog bank, the diagonal scuds that echo the angle of the boat make it look more threatening. The fisherman has to cross the heaving swells to get to his ship before the fog rolls in and puts him at risk of getting lost at sea. He can't lose the weight of the halibut or else he won't get paid and all that work will be for nothing.

Lost on the Grand Banks, 1885

The consequences of getting lost in a fog bank. Two fishermen are lost in a row boat out at sea. We have no idea how this will turn out, it they will survive or perish at sea. Homer gives us no clues. A magnificent painting that contrasts the small boat with the vast distances revealing themselves as the fog clears. A splendidly simple and bare composition.

This painting belongs to Bill Gates.

The Life Line, 1884

One of Homer's most famous and dramatic paintings, and his most famous rescue painting.

A brilliantly simple composition focusing on what was then a new lifesaving technology, the breeches buoy using a cable with a pulley from which hung a lifesaver ring. Crews on either side pulled the cable from a wreck to safety on the shore.

A painting that focuses on a drenched unconscious woman and her savior who remains anonymous behind her blowing red scarf. The waves brushing their feet are really frightening.

Homer's best attempt at a classical painting. It's based on an actual rescue that he witnessed in Atlantic City in 1883. Two lifeguards pulled two drowning women out of the undertow currents near shore saving their lives. Homer worked very hard on this composition reworking it several times. The opinions of critics were mixed, but I think he brought it off very well. A lot of critics (including Henry James) had a hard time reconciling such grandeur of form with (in their eyes) so quotidian a subject. This may be a beach rescue, but it has all the elements of a life and death struggle with the mighty forces of nature that threaten to overpower even the rescuers.

Beginning in the winter of 1884 - 1885, Winslow Homer began to spend his winters in warm tropical climates in the Bahamas, Bermuda, and Florida. Instead of the dramatic stormy skies and slate colored ocean of Maine, he found the brilliant sunlight of the tropics and the sea a bright blue color. By the 1880s, the Bahamas was already what it is now, a vacation destination for affluent older white Americans. Unlike other people vacationing in the Bahamas, Homer was at work. Century Magazine commissioned him to make a suite of watercolors of the Bahamas. Instead of vacationers, Homer concentrated on what was to him a very exotic landscape, and on the people who lived in the Bahamas and made a living from its tropical waters.

Homer was always a great watercolorist, but his Bahamas and Bermuda watercolors have a brilliance and freedom beyond any other American artist of the time, and a lot of European ones too.

The Natural Bridge, 1901, a natural formation in Bermuda. The spread of cerulean blue sea is amazing set off by the spot of brilliant red of the soldier's uniform in the lower right corner. Bermuda was a major British military base at the time.

The Bather, 1899

Once again Homer shows Black people sympathetically, in this case doing the same line of work as the fisherfolk in Cullercoats and Prout's Neck, only now in a tropical environment.

The Turtle Pound, 1898

While sea turtle was already considered delicacy by the people who lived in the Caribbean, these turtles are probably for the export market to satisfy the growing demand for turtle soup in the affluent white populations of North America and Europe.

Palm Tree, Nassau, 1898

Hurricane, Bahamas, 1898

By the 1890s, Homer became interested in the stormy weather that always threatened the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico in the Autumn months. Homer never directly experienced a hurricane, but he marveled at the resilience of tropical communities in the path of such a destructive force of nature.

Shore and Surf, Nassau, 1899

The Coming Storm, 1901

Not in the show, but I think this watercolor in the National Gallery of Art is amazing and so I included it anyway.

One of Homer's best watercolors, what could be seen as the aftermath of The Gulf Stream. The young sailor carried by the storm and beached on some desert island. Is he alive? Did he survive? Homer gives us no answers.

I always marvel at Homer's ability in his watercolors to capture complex light effects, in this case the sunlight after a passing storm, so simply and with such economy of means.

A detail of the painting that I photographed from the original.

The Florida Jungle , 1904

A tangled corner of the Everglades full of implied danger from the teeth of the cougar to the spikes of palmettos.

Hound and Hunter 1892

A very controversial painting with the public when it was first shown. People assumed that the young hunter in the boat was drowning the deer. An irritated Winslow Homer replied that the deer was already dead, and that if it was not the boat would be capsized and the hunter thrown out.

But the public had a point. Homer was an enthusiastic hunter, usually traveling with his older brother Charles and a guide deep into the Adirondack Mountains to hunt deer. The Adirondacks at that time was still very much a wilderness and a large one, a remarkable thing to consider because of their proximity to New York City and the densely populated countryside up and down the Hudson River.

Homer's candor in his hunting scenes struck people then and still does now as cruel.

Late 19th century literate people saw the world in terms that they referred to as "Darwinian," that all life including human society is a constant battle among creatures and people to survive, that in the words of Herbert Spencer, it's "survival of the fittest." This idea preoccupied a lot of artists and writers. Jack London immediately springs to mind, but he was hardly alone (from Hart Crane to Ernest Hemingway).

This "Darwinian realism" got trotted out to justify everything from imperialism to segregation to slavery in the 19th century. It's the heart and soul of the emerging eugenics movement supported by nearly everyone from WEB Dubois and Margaret Sanger to Adolf Hitler. Winslow Homer moved and worked through an atmosphere saturated in such ideas that were very conventional at one time.

And yet, I can't see Winslow Homer enjoying brandy and cigars with Herbert Spencer and his plutocratic friends at Delmonico's as they congratulate themselves for being the summit and center of all nature, the ultimate winners in the struggle to dominate the planet. Homer was resolute in his respect for life's complexity and refused all the facile simplifications of ideology or religious doctrine. He certainly would have found fault with Spencer and company's callous indifference to the struggles of ordinary people.

Hunting Bear, Prospect Rock, 1892

A very anxious looking guide with a hunter hunting the most dangerous quarry of all in the Adirondacks.

This was not in the show, but I include it because it is so marvelous a work of watercolor in composition, technique, color, all of it.

I must admit that I find these last sea pictures with their glimpses of the stormy distances out over the churning water to be disturbing and even frightening.

Right and Left, 1909

One of Homer's last paintings. He died in 1910. Toward the end of his life, Homer's thoughts about the struggle to live seemed to lead him to a chaotic view of nature, that survival and death were ultimately matters of chance, that no matter how much we trimmed our sails and adjusted our ballast a big wave would always swamp our boat in the end. This remarkable painting may be Homer's most distilled expression of that idea. An amazingly imaginative composition puts us literally eye to eye with a couple of golden eye ducks as they fly across the sea waves to escape a hunter's bullet. We see the hunter in a boat in the distance behind the duck on the left firing his gun right at us. One duck flees left and survives, the other flies right and dies. Survival ultimately is a matter of luck and chance.

Some details of this painting that I photographed from the original.

Here is the hunter in the distance firing his rifle right at us. We are the third duck. Do we make it?

The remarkable head of the duck who survives.

The luckless duck who perishes and falls from the sky with all the tragic grandeur of Icarus or Phaeton.

Fox Hunt, 1893

Winslow Homer's largest painting, its composition and sharp contrasts inspired by Japanese prints. How sharply different is Homer's use of Japanese influence from someone like Manet or Whistler. Perhaps Homer's most brutal painting. A desperately hungry flock of crows in the dead of winter on Maine's coast decide to make a meal out of a fox caught off guard. The fox tries desperately to run through the thick snow drifts. I think Homer's sympathies are with the fox. He shows the fox looking into a glimpse of the open sea suggesting escape. Does the fox survive? The always reticent Winslow Homer refuses to satisfy us with an answer. And that perhaps is his point. Such certainties and assurances simply are not there.

It's a hard cruel painting, but as magnificent in its tragic violence as any Death of Hector.

Winslow Homer did not teach much as an artist unlike his contemporary Thomas Eakins who was a very serious lifelong teacher. But he did say to one young artist to save painting rocks for old age because they are the easiest. Homer seems to have taken his own advice.

His last paintings are of the sea crashing on the rocks below his studio in Prout's Neck, Maine.

These last paintings are amazing tours de force of bold painting long before anyone ever thought of painterly abstraction. But they are not abstract paintings but attempts to capture frightful and fatal power of the sea, the origin of life and the final arbiter of what gets to live around and in it. They are nature not as order, but as primordial chaos never tamed by any deity throwing off life and destruction all at once.

The exhibition tried very hard to persuade us to see so very 19th century an artist as Winslow Homer as "relevant." Perhaps they succeeded, but that raises the question of whether or not we are seeing Homer's work as it is or as what we want to see it. Are we reading meanings into Homer's work to satisfy ourselves that aren't really there? Works of art accumulate meanings down through time. Great works of art are always discussed from generation to generation, each new one somehow seeing its own experiences reflected in something that maybe thousands of years old. Homer is not quite so distant from us and we are living with the consequences of things done and left undone in his time. We look at him again because he was interested in a lot of the same things that preoccupy us. We too live in a dramatically transformative time, though how it will transform remains a source of terrifying uncertainty. Will we take a giant leap into a whole new future, or back into an imagined past? Are we about to gamble on science fiction or on nostalgia? Winslow Homer has no answers for us, partly because he's not one of us, and also because he didn't believe in such answers.

We live in a terrifying time of mass death from plague and massacre, where it seems the darkest crypts of the American 19th century are open and the undead from that era swarm the living. Dead Confederates and Kluxers ride shrieking at mid day across our landscape. Our time holds both so much promise and so much peril. Whatever emerges will be nothing like the world we were born into. Winslow Homer through the eloquent bluntness of his work reminds us that it was ever thus.

%20copy.jpeg)

.jpeg)

_in_1919.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20copy.jpeg)

%20copy%202.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment